This article presents in a short, clear and comprehensible way the Greek legal framework of forestry cooperatives and their institutional path through time, since –even if quietly– they perform a serious task and contribute not only to the organization of forestry work but also to the protection of the forest as a common good.

This article deals with forestry cooperatives in Greece. Its aim is to present the Greek legal framework for forestry cooperatives and their institutional evolution over time in a brief, clear, and comprehensible manner. Very little has been written about these cooperatives, which, despite their work, seem to operate quietly and contribute not only to the organization of forestry work but also to the protection of the forest as a common good (Doulakakis, 2013: 104; Fakalis, 2023; Pistolas, 2023; Katsioula, 2023: 52-54). Given the current context, where discussions on cooperatives, and the management and protection of the commons with a focus on the environment has been revived, the study of these cooperatives appears more relevant than ever.1

One might reasonably wonder: what is the relationship between a cooperative, a private enterprise, and forests, which are a common good?

First of all, cooperatives operate across different latitudes and longitudes covering almost the entire spectrum of the economy – from social, insurance, and credit services to agricultural and forestry work. Due to their unique identity, particularly their democratic and non-profit nature, they have also acted in the management of common goods. Specifically, regarding the management of public and non-public forests, forestry cooperatives have developed significantly in countries such as Japan (Ota, 2013), Finland (Pakkanen, 1962), Turkey (Atmiş et al., 2009), and Honduras (Guillotte and Charbonneau, 2020).

Although not widely known, forestry cooperatives also exist in Greece, as 49.3% of the country is covered by forests, most of which belong to the state, while a smaller portion belongs to private individuals, institutions, monasteries, and cooperatives (Chatzopoulou, 2006: 23-24).

Forestry cooperatives are divided into two main categories: compulsory forestry cooperatives and free forestry cooperatives.

Compulsory Forestry Cooperatives: a legislative relic

Compulsory forestry cooperatives are established by law, as stipulated in article 12, par. 5 of the Constitution. Their organization is governed by specific laws and, additionally, by the provisions on agricultural cooperatives. For example, the compulsory law 1627/1939 provides for the establishment of such cooperatives, specifically the formation of compulsory cooperatives of forest landowners (Kassavetis, 2005: 151). Individuals who meet the legal requirements (e.g., co-owners of forest land) are obligated to become members and remain in the cooperative as long as they fulfill these conditions. In these cooperatives, a cooperative share does not correspond to a specific monetary amount but rather to acres of forest land jointly owned by forest landowners (usually under undivided co-ownership status). For example, if one cooperative share corresponds to 1 hectare of forest and a parent bequeaths it to his three children, then, each child, as an undivided co-owner of the forest land, will inherit one-third of the parent's cooperative share and a proportional fractional voting right.2 As a result, these cooperatives have rightly been described as “cooperatives in name only” or “non-genuine” cooperatives (Kintis, 2004; Panagopoulos, 2008), since do not function as voluntary and democratically governed enterprises, according to the international definition of cooperative and, more specifically, the first and second international cooperative principles.3

The main reason for the establishment of compulsory forestry cooperatives was to contribute to the rational management of forest property (Klimi-Kaminari & Papageorgiou, 2010: 119).

However, from the perspective of the European Convention on Human Rights, mandatory participation and continued compliance in a cooperative are not particularly tolerated within our liberal legal tradition (Kassavetis & Douvitsa, 2019). For this reason, the establishment of new compulsory forestry cooperatives is now prohibited, while existing ones continue to be governed by the aforementioned compulsory law and additionally by the previous agricultural cooperative legislation (Article 46 of Law 4423/2016).

Compulsory forestry cooperatives are therefore a legislative relic expected to disappear in the coming decades while it is also possible that the 63 compulsory forestry cooperatives currently registered in the Register of Forestry Cooperatives (RoFC),4 may be converted into free cooperatives. For this reason, we will now focus more extensively on free forestry cooperatives.

Free Forestry Cooperatives: in the shadow of agricultural cooperatives

Free forestry cooperatives are established through private initiative, while both participation and compliance are decided freely by the interested parties. In practice, these cooperatives functioned as a means of organizing forestry work and became synonymous with the scheme of logging cooperatives, later institutionalized with its own legal framework under Law 4423/2016.

However, their institutional path is older, beginning in 1915, when all cooperatives, regardless of the category they belonged to, were governed by the general provisions of Law 602/1915. Since then, any forestry cooperatives that were established operated under this general law, along with specific regulations introduced over time.

The year 1979 marks the beginning of the end of the general law on cooperatives, as a new era in cooperative history was inaugurated: the introduction of specific laws for each category of cooperatives. During this period, forestry cooperatives were overshadowed by agricultural cooperatives. This was likely due to the lack of a clear distinction between forestry and agricultural work/products,5 the dual role of farmer-forestry worker sometimes held by the same person, and their smaller size compared to the strength of agricultural cooperatives. As a result, forestry cooperatives were subject to the laws on agricultural cooperatives (see, for example, Article 1, Paragraph 2 of Law 921/1979), meaning that what applied to the organization of agricultural cooperatives, generally applied indiscriminately to forestry cooperatives as well.

In fact, such was the institutional indifference to forestry cooperatives which continued to be governed by Law 2810/2000 on agricultural cooperatives, even when it was no longer in effect for agricultural cooperatives, as it had been replaced by a newer law (see Article 18, Paragraph 7 of Law 4015/2011).

Over the years, the differences between forestry and agricultural cooperatives, as well as their problems, became more apparent. These circumstances led forestry services to develop a special framework for forestry cooperatives (Explanatory Report, 2016). After multiple delays and changes in governments and ministers, the discussion reopened in 2016, and the preparatory work that had been carried out until then finally reached political attentive ears. As a result, forestry cooperatives acquired their own legal framework, adapted to their specific needs, which was voted in Parliament in a climate of broad consensus and majority approval.

Law 4423/2016 and the organization of forestry work

Law 4423/2016 does not regulate forestry cooperatives in general but a subcategory of them, the Forest Labour Cooperatives (FLC). These cooperatives consist exclusively of forestry workers who collaborate for their mutual livelihood. Both parliamentary discussions and the explanatory report, as well as the provisions of the law itself, indicate that the legislator aimed to organize forestry work and contribute to the protection and regeneration of forests by establishing and developing sustainable forestry cooperatives. Therefore, the legislator conceives the cooperative with a dual mission: both as an institution of workforce self-organization (collective benefit) and as a means of community care (social benefit).

This law fills a legal gap by establishing Forest Labour Cooperatives as a distinct legal entity and by defining the status of forestry worker. However, the requirement for a large number of founding members (21 and above), without exceptions for sparsely populated island and mountainous areas, has hindered the establishment of FLC in these areas (Katsioula, 2023). Additionally, the provision of minimum amount of cooperative share and the legally defined liability limit, work intrusively against self-governance of cooperatives as the above points are internal governance issues which should be decided by cooperative bodies and regulated in their statutes according to the specific needs of the cooperative and its members. Furthermore, since FLC are allowed to distribute profits among their members, they are not different from a conventional forestry enterprise, whose primary goal is profit. Correspondingly, the institutional possibility of distributing the remaining balance to FLC members under liquidation, leaves them vulnerable to bad-faith dissolutions, where current members could exploit the cooperative's wealth, built over decades by previous generations (Mitropoulou, 2016).

Moreover, the law mandates the automatic removal of FLC that are members of agricultural cooperative unions, allowing only networking between similar cooperatives (Article 47, Paragraph 4)6 in contrast to the 6th international cooperative principle, which encourages cooperation among cooperatives. Additionally, this law takes a narrow approach by limiting forestry cooperative exclusively to FLC, without providing for other cooperative schemes, for example, it does not allow the formation of multi-stakeholder forestry cooperatives that could include not only forestry workers but also other interested parties and stakeholders whose economic and social well-being depends on sustainable forest management.

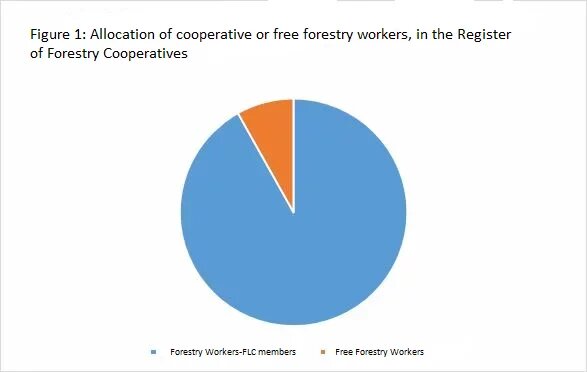

However, this law successfully organized forestry work, as out of the 9.604 registered forestry workers in the Register of Forestry Cooperatives, 8.822 are members of 303 FLC, meaning that 91.8% of forestry workers participate in a FLC (see Figure 1).

On the other hand, FLC do not seem to have been established in island regions, while a significant number of them continues to focus primarily on logging activities, according to an empirical study conducted in 2023 (Katsioula, 2023: 48). Speculation issues have likely not arisen due to their small turnover.

A common resource

In conclusion, the forest is neither a no-go zone nor a museum exhibit to be admired from afar. On the contrary, a forest that is not utilized, not worked, and not inhabited is ultimately abandoned and destroyed (Bampatsoulis, 2016). Thus, the forest is a living, economic, and social resource for our communities, but above all, it is a common resource. With the right improvements to their institutional framework, FLC could be part of approach to forests as a common good. However, they cannot and should not bear the full responsibility for protecting this shared resource on their own. It is therefore necessary to sharpen our legal imagination to provide more comprehensive answers to forest protection and management, not only improving Law 4423/2016 but also institutionalizing the possibility of creating open cooperative schemes with broader composition and more inclusive participation within an overall forest strategy. Otherwise, we will see the tree while losing sight of the forest.

Foreign languages sources:

- Atmiş, E., Günşen, H.B., Özden, S. (2009). Forestry cooperatives and its importance in rural poverty reduction in Turkey. XIII World Forestry Congress 18-23 October, Buenos Aires, Argentina. <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/200470482_Forest_cooperatives_and_its_importance_in_rural_poverty_reduction_in_Turkey>

- Guillotte, C.A., Charbonneau, J. (2020). “Exploring the Links Between the Practices of Forestry Cooperatives and the SDGs”. International Journal of co-operative accounting and management, vol. 3(2). https://www.smu.ca/webfiles/10.36830-IJCAM.20207Guillotte.pdf

- Kassavetis, D., Douvitsa, I. (2019). “The Mytilinaios and Kostakis v Greece case of the European Court of Human Rights: The beginning of the end for the mandatory cooperatives in Greece”. International Journal of Cooperative Law, issue. 2. Ius Cooperativum. https://iuscooperativum.org/issues/

- Ota, I. (2013). “Legal grounds of forest owners’ cooperatives in Japan and their possibilities”. Legal Aspects of European Forest Sustainable Development: Proceedings of the 12th International Symposium in Cyprus (IUFRO Research Group 6.13.00) 96-106 2012.06. https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/pdf/10.5555/20133300961

- Pakkanen, M. (1962). “Co-operative forest industries in Finland”. Unasylva – An international review of forestry and forest products paper, vol. 16(3). Food and Agriculture Organization. https://www.fao.org/3/c3200e/c3200e03.htm

Greek speaking sources:

- Explanatory Report on the draft law “Forestry Cooperative Organizations and other provisions", Hellenic Parliament, 6.9.2016 <https://www.hellenicparliament.gr/Nomothetiko-Ergo/Anazitisi-Nomothetikou-Ergou?law_id=44dc7c48-038a-4ad3-ac54-a6790155864c>

- Standing Committee on Production and Trade, Hellenic Parliament, Continuation of the processing and examination of the draft law of the Ministry of Environment and Energy “Forestry Cooperative Organizations and other provisions (2nd session - hearing of non-parliamentary persons). Draft law: Forestry Cooperative Organizations and other provisions (speech by I. Tsironis, Deputy Minister of Environment and Energy, p. 52 et seq., speech by S. Babatsoulis, President of the Union of Agricultural and Forestry Cooperatives of Evia, p. 27 and 48 et seq.), 13.9.2016. <https://www.hellenicparliament.gr/Koinovouleftikes-Epitropes/Synedriaseis?met_id=f0077232-3f97-43d9-a241-a67f00f4dfe2>

- Doulakakis, N. (2013). The role of the forestry service in the management of forest fires in Greece: Past, present, and future (master's thesis). MSc in Applied Geography & Spatial Planning. Harokopio University. https://estia.hua.gr/file/lib/default/data/8412/theFile

- Kassavetis, D. (2005). Cooperative Institutions: Agricultural Cooperative Organizations (Theory Legislation Jurisprudence). B.N. Katsarou Publications.

- Katsioula, G. (2023). Forestry cooperatives: Economic and social impact and development prospects (thesis), MSc in Social and Solidarity Economy, Department of Social Sciences, Hellenic Open University. https://apothesis.eap.gr/archive/item/178636?lang=el

- Kintis, S. (2004). Cooperative Law I: Introduction - General Part, 4th ed. A. Sakkoulas Publications.

- Klimi-Kaminari, O., Papageorgiou, K. (2010). Social Economy: A First Approach. Hellenic Publishing.

- Mitropoulou, A. (2016). “Commentary on the Proposed Draft Law for Forest Labor Cooperatives”. Social Economy, October 2016 issue, Institute of Cooperative Studies. https://isem-journal.blogspot.com/2016/10/blog-post_66.html

- Panagopoulos, K. (2008). “Differences between compulsory and 'free' cooperatives, especially agricultural” (opinion). Digesta, p. 32 et seq. http://www.digestaonline.gr/index.php/26-2008/154-2008-panag

- Pistolas, G. (2023). Forest Labor Cooperatives (FLC) of Sidirochori and Petrolofos: The unsung heroes of the Evros fire. Website of the forestry office https://dasarxeio.com/2023/09/05/128826/

- Fakalis, T. (2023). “The Heroes of Evros: How two Pomak forestry cooperatives managed to save 100,000 acres – ‘The daily wages from last year’s fire haven’t been paid yet’”, Ethnos, September 20, 2023. <https://www.ethnos.gr/greece/article/280404/oihroestoyebroyposdyodasikoisynetairismoipomakonkataferannasosoyn100000stremmatadenexoynplhrotheiakomatamerokamataapothnpersinhfotia?fbclid=IwAR239DkaeCFeo-pzQU6iU4AqcC1NdvYOyeLiGOGvqoiwInwACnPUqfScE_k>

- Hatzopoulou, I. (2006). Forest Legislation: Critical Review – Jurisprudence. A.N. Sakkoulas Publications.

Footnotes

- 1Indicatively, on November 8-10, 2023, the 3rd International Conference on “Social and Solidarity Economy and Commons” was held at the Instituto Universitário Lisboa (ISCTE-IUL), while on November 24-25, 2023, the 2nd Panhellenic Interdisciplinary Conference on the Commons and Social and Solidarity Economy took place at the Agricultural University of Athens, featuring numerous presentations and roundtable discussions dedicated to this subject. At the same time, on April 18, 2023, the United Nations issued a relevant resolution to promote social and solidarity economy for sustainable development.

- 2See also Article 47, paragraph 4 of Law 2169/1993: «Members of the Compulsory Cooperatives for the management of property under joint ownership and common grazing, as well as the Cooperatives of Forest Owners, are mandatorily all owners of the entire ideal share or a fraction thereof. Holders of the entire ideal share have three votes in the General Assembly”.

- 3For the Statement on the Cooperative Identity of the International Cooperative Alliance, 1995, see https://ica.coop/en/cooperatives/cooperative-identity#:~:text=The%20Statement%20on%20the%20Cooperative,and%20democratically%2Dcontrolled%20enterprise.%E2%80%9

- 4Contact with the Forest Management Directorate, Department of Public Forest and Pasture Ecosystems Management, Ministry of Environment and Energy. Website of Register of Forestry Cooperatives https://mds.ypen.gr/ords/f?p=dd:midaso

- 5During the discussion of the draft bill on FLC in the 2nd session of the Standing Committee on Production and Trade of the Parliament (2016: 52), the then Deputy Minister of Environment and Energy, I. Tsironis, responding to the confusion regarding the difference between forest and agricultural products, underlined that forest products are not identical to agricultural ones, as the former are collection products while the latter are cultivation products.

- 6His objection to the deletion of FLC from agricultural cooperative unions, when this networking is long-standing and positive, was expressed by S. Babatsoulis, president of the Union of Forestry Cooperatives of Evia: “I mean, if the union exists with the financial results I mentioned, with positive balance sheets, with employment, with this and that, it is a contribution of the cooperatives and it exists. It is a company of the cooperatives. I mean, lightly, tomorrow, if the Union goes elsewhere or I am not there or this issue is not resolved, will I go on and delete the fifteen free cooperatives? On the contrary, these people contributed to the creation of this structure, which has a huge property, which has everything”. (Permanent Committee on Production and Trade, 2016: 49).