This article includes preliminary findings from the research project "Gender (in)equality in Greek media & politics" (GenderINmediaGR) by the National Centre for Social Research (EKKE). This project is currently underway and funded by the Heinrich Böll Foundation.

The issue of women’s visibility in the media is key to understanding and addressing gender inequality at the social and political levels. Mass media, after all, form a structural element of contemporary democratic societies, and construct a public space of their own, with multiple and long-lasting effects, as they reach the majority of citizens, contribute in shaping their views and thus affect electoral behaviour. Studies have indeed established that the amount of media visibility politicians and their parties get, as well as the tone with which they are framed, directly affect their appeal to voters and thus their prospects for electoral success. At the policy level as well, the under-representation of women in media more generally, and particularly when it comes to politics, along with the over-representation of men, has been broadly acknowledged as a problem that needs to be dealt with.

Greece stands out as a particularly negative case among European Union (EU) member states when it comes to gender (in)equality. The country had the worse score in the EU in EIGE’s Gender Equality Index in 2022, only to mildly improve in 2023, now ranking 24th among the 27 EU member states. Gender inequalities in Greece are most strongly pronounced in the domain of participating in power and politics more generally, with the country traditionally lagging far below the EU average. Interestingly, the period of the Debt Crisis, that saw a sweeping renewal of political personnel, marked a window of opportunity for the entry of more women in Parliament, increasing their share to 23,3% in 2015 (Q3) 23%, the highest percentage achieved to this day. However, this proved short lived, followed by a steady decrease, only to recently bounce back to.

At the executive level, some previous gains were reversed after the 2019 national election, when the conservative New Democracy returned to power holding an absolute majority in parliament. As noted by Zoe Lefkofridi and Sevasti Chatzopoulou, the percentage of female representation in the first Kyriakos Mitsotakis cabinet fell sharply to just 8.9%, compared to the (already low) 25.5% of the previous cabinet under Alexis Tsipras. Things only somewhat improved in the second Mitsotakis cabinet after the national elections of 2023. Looking at politics at the local level, things remain very poor, with only 1 in 10 candidates being women in the recent local election of 2023. This was reflected in the election results as well, as out of ‘a total of 332 municipalities […] only 22 women were elected mayors,’ while out of a total of 13 administrative regions, there was not even one woman (!) elected as governor. At the European level, where we currently focus our research, the adoption of open lists and a personal preference voting system after the 2014 EP elections in Greece, resulted in the decline of the number of women MEPs.

Of course, understanding gender inequality more broadly, and specifically in the political arena, is a multi-variable task that involves – among other factors – institutional structures and legislation, the agency of political parties and their elites/leaders, political culture and predominant values within a given society, as well as public attitudes and individual electoral behaviour. In our research project (GenderINmediaGR), we focus on one particular area: that of women’s visibility in Greek media outlets during electoral campaigns. Our guiding hypothesis is that potential imbalances in the representation of men and women in the media sphere may affect the behaviour of voters (as they might be inclined to vote for candidates that are more visible), whilst journalistic norms and practices may also be accountable for gender bias. Especially in a country like Greece, with long-standing and persisting problems around gender equality, it is worth establishing whether the media are contributing to this problem or not. Our research takes a first modest step towards addressing this issue within the Greek context.

In what follows, we present some key preliminary findings of our research based on measuring the presence of men and women in TV programmes between the 10th and 27th of May 2024, covering essentially the first half of the campaign leading up to the 2024 EP election (scheduled for the 9th of June). Our sample includes seven (7) TV channels with nation-wide broadcast, including the state-owned ERT, thus covering most of the viewership in Greece, giving us a representative picture of the field.[1] We focus particularly on politicians and candidates for the upcoming EP election, as well as experts/academics and journalists/commentators.

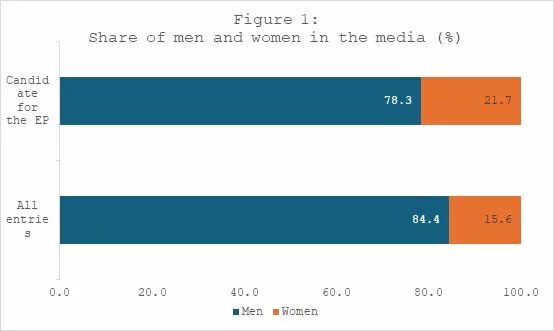

From a first glance at the ‘bigger picture’, the contrast is stark (see Figure 1). Among all categories that have been coded, 84.4% appear to be men, with only a mere 15.6% being women. When looking at candidate MEPs for the 2024 EP election in particular, there is only a very slight improvement, with men at 78.3% and women at 21.7% of the sample, still falling terribly short of any kind of gender balance. Interestingly, the presence of women in Greek media, as measured here, falls right below the percentage of women MEPs elected in the 2019 EP election, that were five (5) out of a sum of twenty-one (21) MEPs, thus representing 23.8% of Greek MEPs. It does, however, mirror a bit more closely the percentage of women elected in the Greek parliament (MPs), that currently stands at 22.7%, which could be an indication that Greek media tailor the presence of men and women in their programmes according to gender representations in national and EU legislatures. Although a ‘chicken or the egg’ question would be perfectly plausible here as well.

Both men and women appear more in the evening news and less in early-morning programmes. Still those few women that make it on TV are more evenly divided between morning programmes and evening news (see Figure 2), whilst men appear much more on the evening news. We assume that this might be related to the tendency for ‘infotainement’ and ‘soft’ news in morning shows, contrasted to the more ‘serious’ or so-called ‘hard’ news of the flagship news programmes of TV channels in the evening, which would seem to further deepen gender stereotyping.

Moving on to further unpacking our sample, we observe that the women that appear on TV programmes are (by order of appearance) mostly Journalists, less so experts, and even less so academics and politicians, with no women at all among trade unionists.

This brief survey of our preliminary findings should make it clear that gender inequality in Greek media poses a major challenge for the country’s democratic politics. Even with a binding gender quota in place, that requires at least 40% of each party list to consist of women, it seems that most of the women candidates are practically rendered ‘invisible’ in the public sphere as they are not featured in relevant TV programmes with national outreach. Even if some of these women are more active on social media, they still enter the electoral race from a significantly disadvantaged position, as their male counterparts enjoy much more visibility in TV shows, which remain by far the dominant news source among citizens/voters according to recent Eurobarometer data.

Taking the above findings into account, along with our overall assessment of the material that we have processed and analysed, we can say with confidence that so far, the electoral campaign that is unfolding in Greece, as reflected in TV outlets, is overwhelmingly male dominated, with women getting substantially fewer opportunities to appear in the media. Moreover, the campaign seems to be centred around party leaders, almost all of them men (with the exception of one woman, Zoe Konstantopoulou, leader of Course of Freedom party), even though they are not candidates for the 2024 EP election, which makes the stark gender imbalance even more pronounced. This, of course, has to do with the fact that treating the EP elections as ‘second order’ national contests finds a rather typical expression in the Greek political context.

It remains to be seen whether this imbalance will be reflected in the over-representation of men among Greek MEPs when the results come in, as it has often been the case in the past. What is certain is that more research is needed to further enhance this quantitative mapping of gender representation/visibility in the media, but also to expand beyond it. Such further research could include qualitative assessments of how male and female candidates and politicians are framed in the media and, even more ambitiously, explorations of possible causal relationships between gender representation imbalances in the media and electoral behaviour.

Findings presented in this article are based on the research project ‘Gender (in)equality in Greek media & politics’ (GenderINmediaGR) that is still in progress. Thus, while they are representative of the timeframe 10-27 May 2024, they are not definitive, as there might be changes/deviations as research progresses and our sample is enriched with more data, covering a broad variety of media outlets and a bigger time-span.

We would like to warmly thank the Heinrich Böll Foundation, Thessaloniki, for funding the project.

[1] To be more specific, we analysed early-morning programmes and evening news programmes of the following TV stations: ERT1, ANT1, MEGA, SKAI, STAR, OPEN and ALPHA.