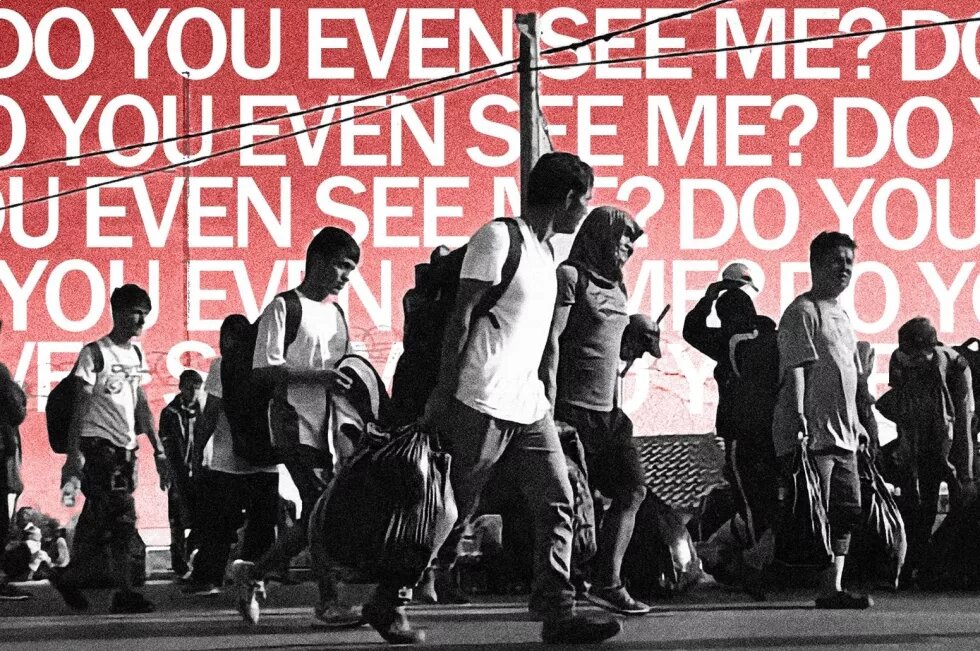

Images are never neutral, photographs are not created in a vacuum; rather, photographs are always already inscribed by the socio-political momentum of their era. Although we live in a hyper-visual world, we often have little visual education in order to take a critical stance on how we look when we gaze at images—or, on what it means to avert our gaze and stop looking—particularly images of “crisis,” violence, displacement, and war. We focus on watching photographic images because, as we have seen over the past eight years, through the use and control of photography states seek to generate consent to the necropolitical management of “crisis”, to the undeclared war against refugees. We argue that by watching photographs, as opposed to merely looking at them, we can inhabit a queer feminist perspective that seeks to abolish state-imposed divisions between “refugees,” “migrants,” and “citizens.”

So, let’s start by closing our eyes and thinking about the so-called “refugee crisis.” What is the first image that comes to your mind? It might be the photograph taken of the body of the little toddler Alan Kurdi on a beach near Bodrum, Turkey, who, along with his family, drowned attempting to make the Aegean sea crossing.

For the past five years when we have googled the term “refugee crisis,” the image below was always the first or the second search result.

Massimo Sestini’s award-winning photograph entitled “Rescue Operation” was shot 25 kilometres from the Libyan coast and depicts from above a boat full of people before they were intercepted by an Italian navy ship during Operation Mare Nostrum.

It is similar to so many other images shot in the same period near the coastline of Lesvos, depicting people making the sea passage between Turkey and Greece. The declaration by European authorities of the “refugee crisis” coincided with the circulation of such images, myriad images of people in boats attempting to reach, or arriving on what is claimed as “European soil.” At the time, a journalist claimed that this was the most photographed crisis in human history.[1] The appearance of people arriving in Europe to seek international protection signalled the beginning of the “refugee crisis” for the supranational union and its member nation-states. In a book we wrote together,[2]we suggested that the appearance (and disappearance) of people seeking asylum was closely related to the appearance and circulation of images of arrival. First people whom the state calls (or refuses to recognise as) “refugees” appeared at the shores of Lesvos, and then images of them approaching the shores appeared in the media.

If this series of appearances signals the beginning of the “crisis,” one might wonder whether disappearance would signal the end of it. In fact, the opposite is the case: the absence of photography has been a key facet of the necropolitical bordering of Europe, which is the reality that crisis narratives invert. People are made to disappear during pushbacks[3] and “driftbacks”[4] and through consequent shipwrecks caused by the Hellenic Coast Guard and Frontex, such as the horrific massacre, which occurred off the coast of Pylos on 13 June 2023, taking 600 lives, the deadliest known shipwreck in recent years.[5] Witnesses among the 104 survivors of the shipwreck who were aboard the Adriana attest that the Hellenic Coast Guard made “multiple failed attempts to tow the boat, which ultimately destabilised it and led to its capsizing.”[6] Seeking to evade accountability, the Coast Guard claims that photography that night was impossible due to equipment malfunction; but the authorities also confiscated survivors’ mobile phones, seeking to disappear what they had photographed with their cameras.[7] Loved ones of the survivors who visited them behind bars were forbidden to take or keep their photographs; journalists photographed survivors and their loved ones reuniting, trying to embrace each other through the metal bars the Greek state put between them.[8]

Image credit: 2023 Reuters/Stelios Misinas

Reproduced by Human Rights Watch, 202312eca_greece_shipwreck_survivor.jpg

It is not a coincidence that pushbacks constitute what the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights has called “concealed state policy.”[9] As with photography bans in place in camps,[10] the attempt of the state to control the field of photography in producing an aqueous cemetery of the Aegean sea—one of the most dangerous border crossings globally—and of the Evros river, parallels, secures, and reproduces a border regime of enforced disappearance. This regime declares and signifies its own crisis through images of appearance, which is to say: survival, life. If the visual signifiers of the “refugee crisis” are images of people arriving by boat in Europe, these people’s arrival being the crisis. A mainstream visual narrative of the crisis projects implies that when the people stop arriving in boats the “crisis” will be over. Although it does not depict these practices (of interceptions, pushbacks, shipwrecks, drownings, shootings, pushing people overboard, and other state violence at sea), and even censors such depictions, this mainstream visual narrative nevertheless signifies a necropolitical regime of killing and letting die people crossing borders without state authorisation and to seek asylum.

Images are never neutral, but especially not when they are signifiers of political phenomena, of violence and power, of subjugation and dehumanisation. Sestini’s image is shot from above, whilst the photographer is on a helicopter, embedded with the authorities, flying above the boat. This “bird’s eye view” already positions the viewer at a distance and above the people depicted in the image. This would have been a completely different image if the photographer was in the boat: the viewer would then be positioned eye-to-eye to the people in the boat, see their expressions, perhaps their fear and hopes. Usually super-powers such as God or the state are granted with this view from above: this ever-present eye in the sky that observes and sees and therefore knows everything—or aspires to that totality. In Sestini’s photograph, we are invited to see through the eyes of the state, and we are offered a power of observation from above. This is extremely problematic, as it seeks to foreclose the possibilities of empathy and human connection. EU border enforcement increasingly relies on air surveillance because unlike sea vessels, aeroplanes do not have an obligation to undertake sea rescue.

Our discussion of the power relations inscribed in this photograph raises the question: who has the right to look at whom, under what conditions? As the late bell hooks has shown in her book, Black Looks: Race and Representation, over the centuries of ongoing white supremacy, one of the well-known tortures that enslaved Black people suffered was the denial of their right to look: not only through torture devices that restricted their peripheral vision, but also through laws that criminalised Black people looking white people in the eyes.[11] Slavery and post-slavery regimes sought to restrict and forbid the right to look, and slavery economies sedimented globalised structures of racism that inform “looking relations” to this day.

Images may prevent us from perceiving phenomena, through their presence as well as their absence. Viewing an image and believing it depicts a particular reality, may be as misleading as having no images at all to view. How do we cultivate collective perceptual practices in order to critically approach how we look at photographs, not just for what they depict, but also for what they do not: what lies beyond the frame?

If the visual is a field over which the state tries to gain or maintain control, we also recognise the potential of the visual to be reclaimed as a space of resistance, of production of counter-meaning. Ariella Aïsha Azoulay has argued that we can resist the state’s attempt to gain the monopoly of meaning by shifting from merely looking at photographs in all the ways we were schooled to look through the eyes of the state, to watching photographs: understanding that photographs call us to responsibility, to confront and resist war, violence, occupation, genocide, unfolding in front of our eyes, but also—variously—obscured, aestheticised, or excised by the frame.[12] The collective shift from looking to watching would dramatically alter the ways we perceive not only photographs and images, but our bodies, our positionalities, our relationalities. In a time of war, genocide, occupation, and displacement, reclaiming our collective vision requires acts of daily resistance.

[1] Jerome Phelps (2017) “Why Is So Much Art about the ‘Refugee Crisis’ So Bad?” Open Democracy, 11 May 2017, last accessed 14 December 2023, www.opendemocracy.net/en/5050/refugee-crisis-art-weiwei/

[2] Anna Carastathis and Myrto Tsilimpounidi (2020) Reproducing Refugees: Photographia of a Crisis. London: Rowman and Littlefield International.

[3] European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights (2022) Analyzing Greek Pushbacks: Over 20 Years of Concealed State Policy Without Accountability. Last updated 22 February 2022, https://www.ecchr.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/Analyzing_Greek_Pushbacks-_Over_20_years_of_concealed_state_policy_without_accountability.pdf

[4] Forensic Architecture (2020–) Drift-backs in the Aegean Sea, last accessed 14 December 2023, https://forensic-architecture.org/investigation/drift-backs-in-the-aegean-sea

[5] Feminist Autonomous Centre for research (2023) Abolishing Borders, Ending Violence, Transforming Justice: Feminist No Borders Summer School Statement on the Pylos Shipwreck, June 2023, last accessed 14 December 2023, https://feministresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Statement-Signatures.pdf

[6] Forensic Architecture (2023) The Pylos Shipwreck, last accessed 14 December 2023, https://counter-investigations.org/investigation/the-pylos-shipwreck

[7] Human Rights Watch (2023) Greece: 6 Months No Justice for the Pylos Shipwreck, 13 December 2023, last accessed 14 December 2023, https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/12/13/greece-6-months-no-justice-pylos-shipwreck

[8] InfoMigrants (2023) Syrian brothers embrace after reuniting in Kalamata, 20 June 2023, last accessed 14 December 2023, https://www.infomigrants.net/en/post/49780/syrian-brothers-embrace-after-reuniting-in-kalamata

[9] European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights (2022) Analyzing Greek Pushbacks: Over 20 Years of Concealed State Policy Without Accountability. Last updated 22 February 2022, https://www.ecchr.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/Analyzing_Greek_Pushbacks-_Over_20_years_of_concealed_state_policy_without_accountability.pdf

[10] Anna Carastathis and Myrto Tsilimpounidi (2023) “Through the lens of a refugee: Disrupting visual narratives of displacement.” In The Routledge Handbook of Refugee Narratives, edited by Evyn Lê Espiritu Gandhi and Vinh Nguyen. London: Routledge, pp 115–127, https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/oa-edit/10.4324/9781003131458-13/lens-refugee-anna-carastathis-myrto-tsilimpounidi

[11] bell hooks (1992) Black Looks: Race and Representation. Boston: South End Press.

[12] Ariella Azoulay (2008) The Civil Contract of Photography. London: Zone Books.