Changing national laws and policies is cumbersome, time-consuming and risky: what if the law or policy proves to be a dud? Cities, on the other hand, can be a hotbed of innovation. They are big enough to try out new ideas on a large scale, but small enough to brush them aside if they do not work out – and the best ideas can be scaled up to the national level.

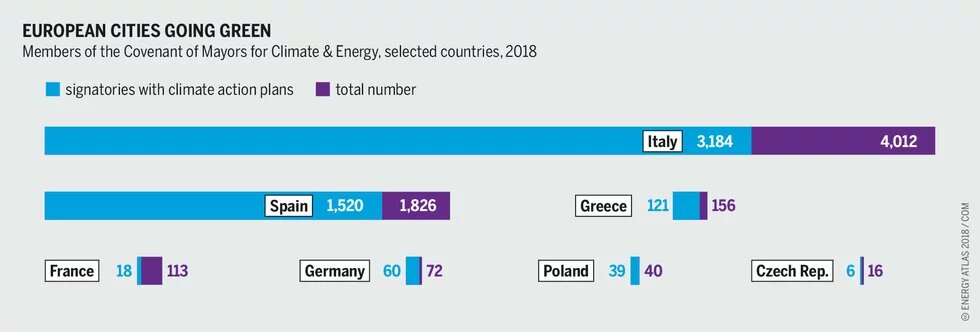

Cities have become front-line players in efforts to adapt to and reduce the impact of climate change. Agenda 21, passed at the Earth Summit in Rio in 1992, called for action to promote sustainable development at all levels, from international down to local. Since then, cities have made big strides in this direction. At the European Parliament in 2009, hundreds of European cities undertook to reduce their CO2 emissions, and launched the EU Covenant of Mayors movement. This has since spread worldwide, bringing together over 7,700 local authorities committed to energy and climate action. During the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris in 2015, close to 1,000 local leaders pledged to make their cities carbon-neutral by mid-century.

Cities consume over two-thirds of the world’s energy and account for some 70 percent of its CO2 emissions. They both contribute to climate change and are victims of its impacts. Cities suffer from flooding, rising sea levels, landslides, and extreme heat and cold. They are affected by water shortages, smoke from wildfires, and migration of rural residents as a result of climate change in surrounding rural areas. Faced with these challenges, as well as existing environmental problems such as air and water pollution and waste disposal, cities have huge incentives to address climate change.

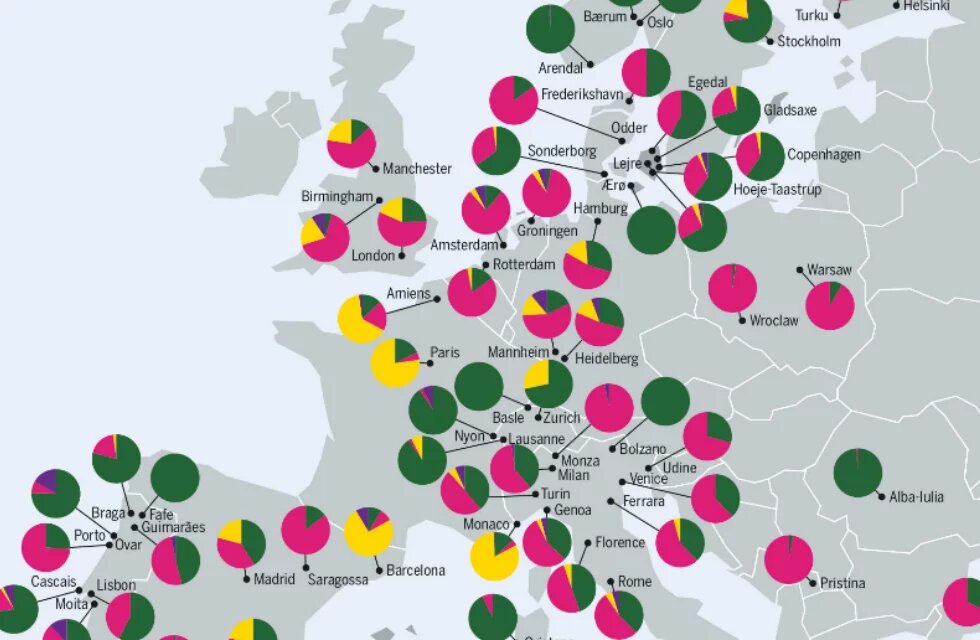

As part of Europe’s energy transition, local authorities have tried to reduce the impact of climate change in high-profile ways: by promoting renewable energy technologies, by exploiting big data, and by developing smart power grids. But the question of who will own, control and benefit from this wave of new technologies is overlooked, and remains unanswered at the national and EU levels.

Cities are coming up with responses. The administrations of Barcelona, Paris and Ghent, for example, are reconsidering the notion of energy as a “commons ”: energy sources such as the wind, sunlight, hydro, biomass and geothermal are natural resources, so should be treated as common goods and allocated to benefit society as a whole, not a small number of individuals. The shift from an extractive to a regenerative economy can make sharing such resources more equitably possible. In the UK, more and more local authorities are tackling “fuel poverty” (inability of people to keep their home warm at a reasonable cost) by putting energy management back into local, public hands.

Bristol promotes projects that aim to reduce energy use (for instance by insulating buildings) and generate renewable energy.These initiatives are firmly linked to a local currency, the Bristol Pound, whose objective is to strengthen the local economy by keeping money circulating within the city. In October 2017, Paris, Copenhagen and Oxford announced plans to ban petrol and diesel cars, well before national bans come into effect. In the Netherlands, “gas-free” districts were established before the government decided to phase out the use of gas for cooking and heating.

More and more local authorities are helping citizen-driven energy projects get off the ground, either by investing directly in local energy cooperatives, or by providing subsidies, legal and technical expertise, and access to public facilities. Rather than seeing the energy transition as a problem, they see opportunities for regional economic development. They find access to new capital by tapping into local savings and generating revenue streams that benefit the local community instead of a handful of distant shareholders.

They influence the financing of energy by issuing “green bonds” (bonds used to finance environmental investments) and by bulk-buying power to cut costs. Revolving funds encourage energy saving: municipal departments that conserve energy are permitted to keep part of the savings to spend on other initiatives. Litoměřice, a town in the Czech Republic, is one of many local authorities that have successfully introduced such a scheme. Paris has outlined crowdfunding as a key strand of its 2050 climate-neutral strategy and has announced plans to become an international hub for green finance.

The EU’s Clean Energy package of 2016 will influence the energy landscape for decades to come. It will determine whether local authorities, citizens’ cooperatives and other new actors are given fair access to the market, alongside the current dominant players. Technology-enabled, decentralized energy systems can only grow to their fullest potential if these decentralized actors are empowered. This calls for the introduction of new, multi-level governance models, better adapted to the challenges of tomorrow’s energy system.

In January 2018, the European Parliament voted to ask EU member states to set up permanent energy and climate dialogue platforms with citizens and local authorities. These will give local authorities the opportunity to play a central role in the energy transformation.