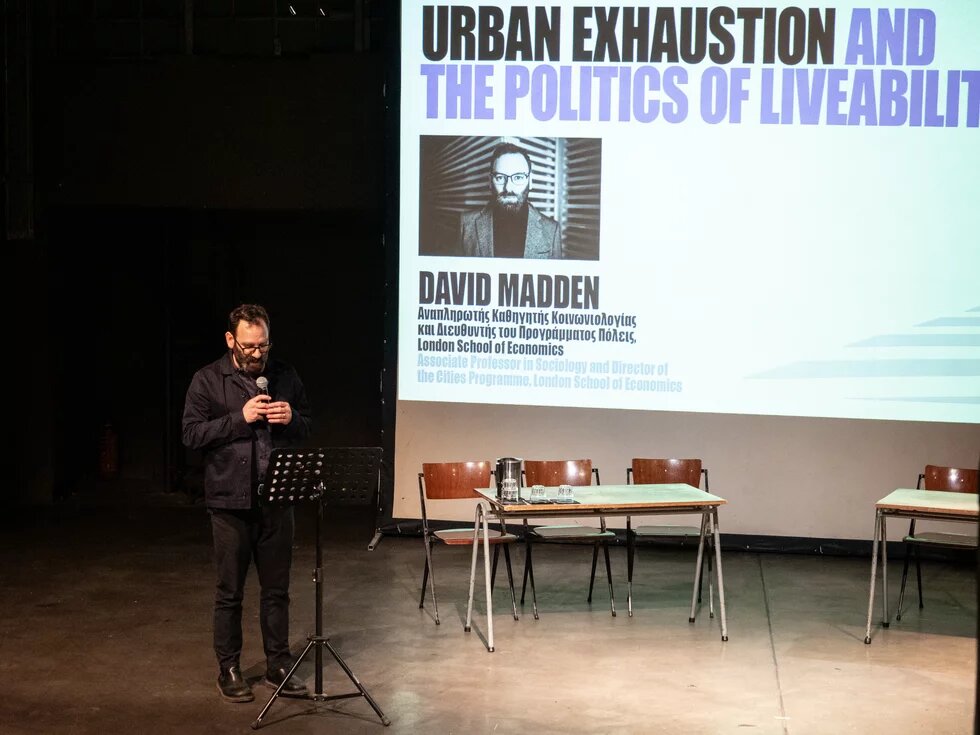

“Why are our cities unbearable?” This was the question that the Heinrich Böll Foundation – Thessaloniki Office sought to answer during the event it organized on December 14, 2024, in Athens, with keynote speaker David J. Madden, Associate Professor of Sociology at the London School of Economics and an expert on contemporary urban issues. The event also aimed to explore the conditions for a different, sustainable urban daily life, especially in Greece, through a panel discussion featuring Eva Grigoriadou, Alexandros Kioupkiolis, Petros Kokkalis, Loukas Triantis, and Sofia Tsadari.

Let's start with something simple and true: cities were created to fulfill people’s desire for a good life. Much has been said and written about the philosophical quest for the ideal city. The ideal city may seem utopian, but it is the one that points the way forward and at least defines the boundaries between a sustainable or an unsustainable city.

All the more so in an era when people are beginning to feel or are becoming victims of the city, when the organism of the city starts to attack them, to devour them, when citizens are, or suspect they are unhappy in their daily lives, which they would like to change but lack the strength to fight for something better on their own.

“Why are our cities unbearable”? This is precisely the question the Heinrich Böll Foundation – Thessaloniki Office attempted to answer with an event it organized in December 2024. The keynote speaker was David J. Madden, Associate Professor of Sociology and director of the renowned “Cities” program at the London School of Economics and Political Science. In recent years, through the publication of articles and books, Madden has made a significant impact not only in academic circles but also within social movements, opening a new global approach to urban issues.

David Madden on urban exhaustion

David Madden’s speech revolved around the syndrome of the tired metropolis and urban exhaustion, as well as the class dimensions of the phenomenon. As he initially stated, the crucial issue is to define what exactly urban sustainability is and how it functions in real terms in contemporary cities. He made it clear that he rejects notions that adopt urban triumphalism or elitist approaches to the sustainability of cities. “Cities undermine sustainability in many ways. We must, however, focus the discussion on the urban working majority, which the urban development model has failed to serve properly over the past 40 years”, he emphasized. This, he said, is a model that has fostered conditions of inequality and injustice, ultimately making life in the city unlivable for the have-nots.

“And this reality manifests as a widespread sense of exhaustion and fatigue among people. We're talking, therefore, about ‘urban exhaustion’. Something that helps explain the contradictions and crisis of the late neoliberal city”, he stated. Urban exhaustion is not just an impression. It translates into negative effects on the mental health of the have-nots. And all of this is happening because cities have become, more than ever, more unjust, more expensive, more inaccessible with fewer public infrastructures, fewer social networks, and a more competitive lifestyle on an economic and social level. Cities where workers never stop working all day and every day, harder and harder, just to maintain what they’ve achieved, and where rest has become a luxury. At this point, he also recalled philosopher Nancy Fraser’s assertion that “modern capitalism cannibalizes society”. It is, he said, like a snake devouring its own tail.

The feeling of urban exhaustion is multifactorial and can be found across a wide spectrum, from domestic to political exhaustion. David Madden spoke about the difficulty of managing a household due to lack of free time, the absence of care, the high cost of housing and rising housing insecurity, the environmental crisis, the crisis of trust in the state, and the lack of public spaces. He also brought the pandemic into the discussion, emphasizing how it blurred or even erased the boundary between home and work, further fueling the trajectory of exhaustion.

And the question arises: Can this reality be changed? Can there be a sustainable city for every citizen? “The clearest way to make a modern city less exhausting is to support movements that demand a more humane housing system”, Madden underlined. As examples, he pointed to the demand for social housing, which is becoming massive again in various countries, including in Europe as well as the Utopias community centers in Mexico.

“We need to redistribute sustainability. This might mean that a city must become less sustainable for people at the top of the economic hierarchy. But I believe we can only create an alternative form of sustainability by directly confronting this inequality. We must stop subsidizing the sustainability of the few through the exhaustion of the many”, Madden concluded.

The situation in Greek cities

But how do Greek cities experience exhaustion? Which different characteristics might they possibly have? What traces has the neoliberal policy model left upon them? And what conditions could serve a different everyday life?

These issues, among others, were at the heart of the discussion that followed, which picked up the thread from David Madden’s speech focusing on the Greek reality. The panel included Eva Grigoriadou, architect and founding director of the research group URBANA, Alexandros Kioupkiolis, professor in the School of Political Sciences at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (AUTH), Loukas Triantis, assistant professor at the School of Architecture, Department of Urban and Regional Planning at AUTH, and Petros Kokkalis, secretary of KOSMOS and former Member of the European Parliament. The discussion was moderated by Sofia Tsadari, PhD architect and urban and regional planner (National Technical University of Athens - NTUA), and a member of the interdisciplinary design cooperative Commonspace Co-op.

First of all, the connection between the policies of neoliberalism and urban exhaustion became common ground for all the speakers.

What about the specific “flaws” of a Greek city? All citizens experience these, elsewhere more (Athens, Thessaloniki), elsewhere less… A characteristic example is a random sidewalk in the center of a random city, where what happens reflects the worsening living conditions, according to the description by Alexandros Kioupkiolis: broken tiles, gaps, holes, occupation by outdoor seating and other objects, parking cars, delivery motorcycles cutting through. “A jungle on top of the most basic condition a city should have: the ability to walk safely on a sidewalk”, he emphasized. And when a municipality decides to fix and widen the sidewalk, as well as reduce car traffic, what happens? “Property prices rise, residents with middle and lower incomes are forced to leave the area and move to more degraded areas. And ultimately, they won’t have access, due to an insufficient transportation network, to the parts of the city where the sidewalk has been built”.

Greece, however, presents some additional, aggravating factors. It is a country that experienced for many years a policy of strict austerity, which led to the weakening of public infrastructure and the intensification of inequalities. It is also a country where local government is weakened by the central administration's choices, and where the scope for decision-making by the city itself, that is, by a municipality, is limited. These two conditions increase citizens' frustration and ultimately reinforce the feeling of political exhaustion.

“Municipalities in Greece have the least capacity, authority, and resources to do anything. This is a very specific political choice. In the rest of Europe, on average 18% of the budget goes through the municipalities. In Greece, this percentage is 4%-5%. There is a reduced autonomy of local governments”, mentioned Petros Kokkalis.

Alexandros Kioupkiolis reminded us of something important: that urban exhaustion is not a modern phenomenon. Life in the industrial cities of the 18th or 19th centuries, for example in England, was harsh and exhausting for the social majority. However, today there is a crucial difference: “There is no horizon of expectation for something better, as there was back then. In his essay The Burnout Society, Byung-Chul Han writes that this expectation for something better, which would give meaning to the world, has been lost. Industrial societies had the vision of progress and collective emancipation: ‘We struggle today, but future generations will be better off’. This has been lost, leading to even greater alienation, and the difficult conditions in the city are becoming even worse.

Alternative prospects

So, where do we go from here? How can cities become sustainable?

According to Loukas Triantis, a necessary step is identifying inequalities and then adopting targeted policies. For instance, one major inequality relates to housing, which is becoming increasingly urgent in Greece. “We need to look at policies that ensure affordable housing, that treat housing in some way as a right and not as a commodity”, he stated. Petros Kokkalis considered the European Green Deal, although its strategies “originate from a neoliberal European Union”, as an opportunity for the country and its municipalities to address social inequalities, among other things. However, he emphasized that Greece “does not implement planning and participatory democracy in the same way other countries do”.

For Alexandros Kioupkiolis, a fundamental condition for more humane cities is a shift in the balance of power at various levels. “Good policies to address inequalities can exist. The issue is their implementation”, he noted.

And this is precisely where the concept of participatory planning comes into play.

“We need to build a city that takes care of us, where we feel safe and that helps us to take care of other people”, said Eva Grigoriadou, emphasizing inclusivity and the gendered dimension of care. “Everything should be done through participatory processes within neighborhoods. Unfortunately, participatory planning is at very low levels in Greece, with municipalities undermining these processes”, she added, sharing her perspective based on her experience and involvement in inclusive participatory urban planning. She also noted that citizens –especially women with whom URBANA works– “are willing to participate, to talk about their experience in the city and to plan. But if even a small change doesn’t occur, then fatigue, discouragement, and a feeling of frustration will follow”.

Alexandros Kioupkiolis spoke of a veiled or guided form of citizen participation in policy planning and decision-making by municipalities. According to him, what is needed is the self-organization of society and the mobilization of social forces to have an actual impact on the planning and implementation of urban policies. “We need what we call counter-hegemonic action”, he emphasized, so that pressure can be exerted by the citizens themselves on local authorities.

Loukas Triantis argued that both genuine administrative decentralization and the institutionalization of public participation are critical issues. “We need to strengthen the institutional framework for participation. And I agree with what was said about collective action, that change must come from society itself”. Finally, he addressed the concept of redistribution: “There are entire areas in Athens facing issues of social deprivation. And there are also areas that are more vulnerable to climate crisis, to floods or fires. It is important to find ways to redistribute, whether on a large or small scale, within the framework of urban governance. Because that’s how we can address inequality”.

So, cities are, are becoming, or will become exhausted organisms. And like every organism, if it doesn’t develop defenses, if it doesn’t react, if it doesn’t fight back, it simply dies...