As this article points out, the Green Deal provides a great opportunity to re-examine the issue of "cities vulnerable to risks" with fresh eyes, by applying good risk management practices embedded in the instruments that will be used to tackle climate crisis.

In 2019, the EU announced the plan of the so-called “European Green Deal”, which aims to transform the EU into a just and prosperous society, where by 2050 net greenhouse gas emissions will be zero and economic growth will be disconnected from use of resources. It is important that Green Deal also aims to protect, conserve and enhance the EU's natural capital as well as to protect the health and well-being of citizens from environment-related risks and impacts. At the same time, transition should be just and inclusive, leaving no one behind. The Commission recognises that the enhancement of climate protection efforts, resilience building, prevention and preparedness are all crucial.

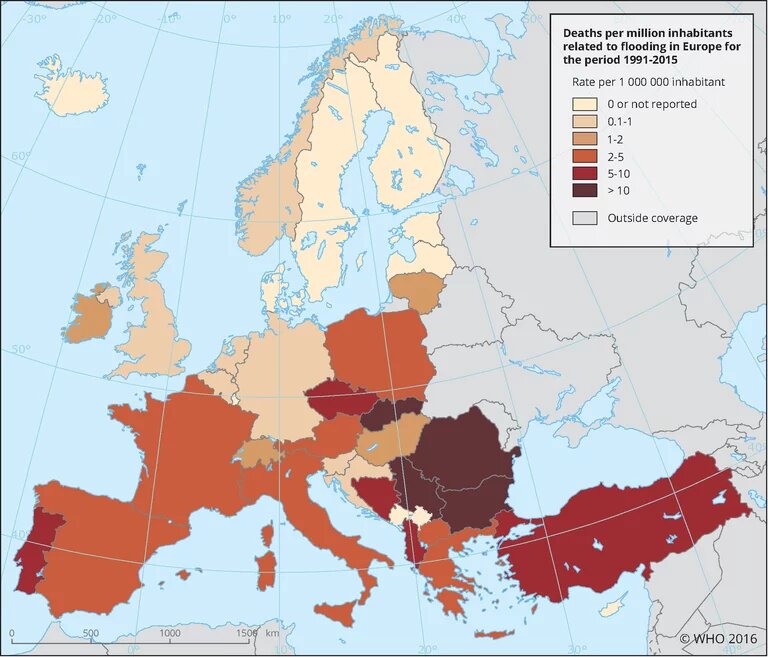

So far, discussions, proposals and actions have mainly focused on the first part, having rather neglected the second which refers to environmental/natural hazards and protection from them. However, the older as well as the most recent experiences regarding the impact of environmental risks are quite bitter. In Greece, there are many recent examples: The earthquake that struck Athens (Parnitha) killed 143 people, just 18 km from the Acropolis, and created a direct financial cost of about 3 billion dollars, the largest ever caused by a natural disaster during the country’s recent history. This was followed by the big fires of 2007 with 85 victims, the floods in Mandra and the surrounding area (2017, 24 victims), the fire in Mati (2018, over 100 victims), the storm in Halkidiki (2019, 7 victims), the flood in Evia (2020, 8 victims) and then in Karditsa where the passage of Ianos left behind human victims, and major damage to buildings, infrastructure and cultivated areas with an immediate economic cost of at least 200 million euros. The reminder that the country is, and will continue to be, in danger is very clear. But in the rest of Europe the experiences are just as tragic.

A common characteristic of all these disasters seems to be the vulnerability of our cities and settlements, which are often built, developed and extended in unsuitable soils, on muddy torrents, and even in river delta formations. Cities and settlements are quite often structured with spatial and urban planning that dramatically increase their exposure and vulnerability to natural hazards, with the case Mati area to be an extreme example. Buildings are often illegal constructions and therefore extremely vulnerable to earthquakes, such as in the western suburbs of Athens in 1999. This does not mean, however, that the civil protection system has been flawless in all previous cases. On the contrary, with the village of Mati as an extreme example again, in recent years the most negative features of an outdated and ineffective civil protection system have emerged.

Green Deal in combination with Greece's recovery and resilience plan provide a great opportunity to re-examine the issue of “cities vulnerable to risks” with fresh eyes, that is to say, with the possibility to apply good risk management practices in the instruments that will be used to tackle climate change. The urban and spatial planning included in the service of dealing with the climate crisis is at the same time extremely beneficial in the prevention and reduction of natural hazards, such as earthquakes, floods, forest fires, etc.

“Climate ambition” project includes actions of “Land Use-Land Use Change” as well as the EU forestry strategy. In this context, the plans can incorporate provisions aimed at reducing forest fires and floods.

The new “renovation wave” initiative in the building sector and the challenge of improving the energy efficiency of buildings, can be well combined with testing their resilience to natural hazards. The earthquake risk assessment of the approximately 80,000 public buildings in our country has been at a standstill since 2001. A strong “wave” of renovations can drastically accelerate the earthquake risk assessment, if the two actions are combined in a coordinated synergy. Particular emphasis must be placed on buildings and facilities of strategic importance, the uninterrupted operation of which is always imperative for the economy and society (e.g. power stations, telecommunication stations, etc.), not only in normal conditions but also during catastrophic events. The corresponding “wave” of renovations in private buildings can be an incentive to launch a major project for earthquake risk assessment in private buildings, an issue that has never been discussed in the country. Needless to mention at this point, the special need to protect the places of cultural value such as archeological sites, monuments and museums against these risks.

After the tragic tsunami of 2004, which killed more than 220,000 people in the Indian Ocean area, it was realised that this danger, although not common in Europe and the Mediterranean, it threatens this region too. Because, when the extreme phenomenon occurs, the consequences will be tragic, if there is no previous preparation. Despite early warning systems developed under the auspices of UNESCO and with know-how produced mainly under EU programmes, other measures are recommended, such as informing the public. However, the recognition of coastal spatial planning as an important factor that increases or decreases exposure to risk and vulnerability has been neglected. Proper spatial planning actions can save many lives tomorrow, especially where there will be no large concentration facilities for people with reduced mobility, e.g. hospitals, schools for young children or nursing homes in high-risk coastal areas.

Green Deal provides for the development and utilisation of digital and other new technologies. These are indeed absolutely necessary to support the diverse actions aimed at organising new standards for cities and settlements in the context of a long-term and effective plan to reduce natural hazards. But the development and application of technologies is fully intertwined with research and innovation, which, according to Green Deal, will be drastically enhanced, e.g. through “Horizon Europe” programme, with four main missions in areas such as climate change adaptation, oceans, cities and land. Our country, unfortunately, has been ranking close to bottom in the field of research within the EU27 for years, both in terms of funding as well as drawing up and implementing a coherent plan for research and innovation with priorities, goals and pace for achieving these goals. Drastic institutional interventions are needed here. Unfortunately, the Greek recovery and resilience plan does not leave much room for optimism in this area.

Exactly two years ago, I proposed the need to plan a “European Charter of Civil Protection”. Developments are underway, so today we can renew and update our proposal and talk about a “European Charter for the Protection from Environmental Risks” as a necessary component of Green Deal.