This article proposes gender mainstreaming within recovery plans and the Green Deal, as well as new tools to promote equality.

Gender inequalities were significant even before the pandemic. The Covid-19 crisis reinforced discrimination and gender inequalities, both because of the pre-existing discrimination and the disproportionate impact of the crisis and measures on women. Pandemic recovery is an opportunity to accelerate progress and deliver results in terms of gender equality as well.

Gender inequalities in the EU and Greece

According to EIGE’s Gender Equality Index Report 2020, improvement on equality issues is very slow across the EU, with some countries doing a little better and others lagging far behind. The index score grows by an average of 1 point every 2 years. At the current rate, it will take more than 60 years to achieve gender equality in the EU. The biggest improvement has been in decision-making, which has been driving most of the change in the Gender Equality Index. Since 2010, “the domain of power” has contributed 65% of the total gain in gender equality in the EU. To a significant extent, this is due to legislative measures and other policy actions.

Greece ranks last in the Gender Equality Index, with 52.2 points out of 100, 15.7 points below the European average. Its score remains roughly the same since 2010. The pandemic crisis, as expected, has worsened the situation.

Greece's highest scores are recorded in the domains of health (84.0 points) and money (72.5 points). In both these areas, Greece has one of the lowest scores among all countries (ranking 21st and 22nd respectively). Gender inequalities are more pronounced in the domains of power (27.0 points), time (44.7 points) and work (64.4 points). In these areas, Greece's performance is also low compared to other Member States (ranked 27th in all three). Since 2010, Greece's score has improved mainly in the domains of time (+9.1 points) and power (+4.7 points). Since 2017, Greece's score in the area of power has increased by 2.7 points. On the contrary, since 2010, Greece's scores have decreased in the domains of money (-2.8 points) and health (-0.3 points), while stagnation is recorded in work (+0.8 points).

The impact of the crisis on women

Many international organisations, including the EU and the UN, as well as the International Monetary Fund warned as early as spring 2020 that women had been and could be severely affected by the pandemic. Examples of the disproportionate impact of lockdown policies on women and girls unfortunately abound:

- One million women in Japan left the labour market when the pandemic hit, while men's participation in the workforce changed much less.

- In Chile, 76% of women reported spending more time on household chores since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic.

- In Mexico, the emergency calls related to violence against women increased 53%.

- The Malala Fund estimates that 20 million girls in developing countries may never go back to the classroom after a pandemic-related school closure.

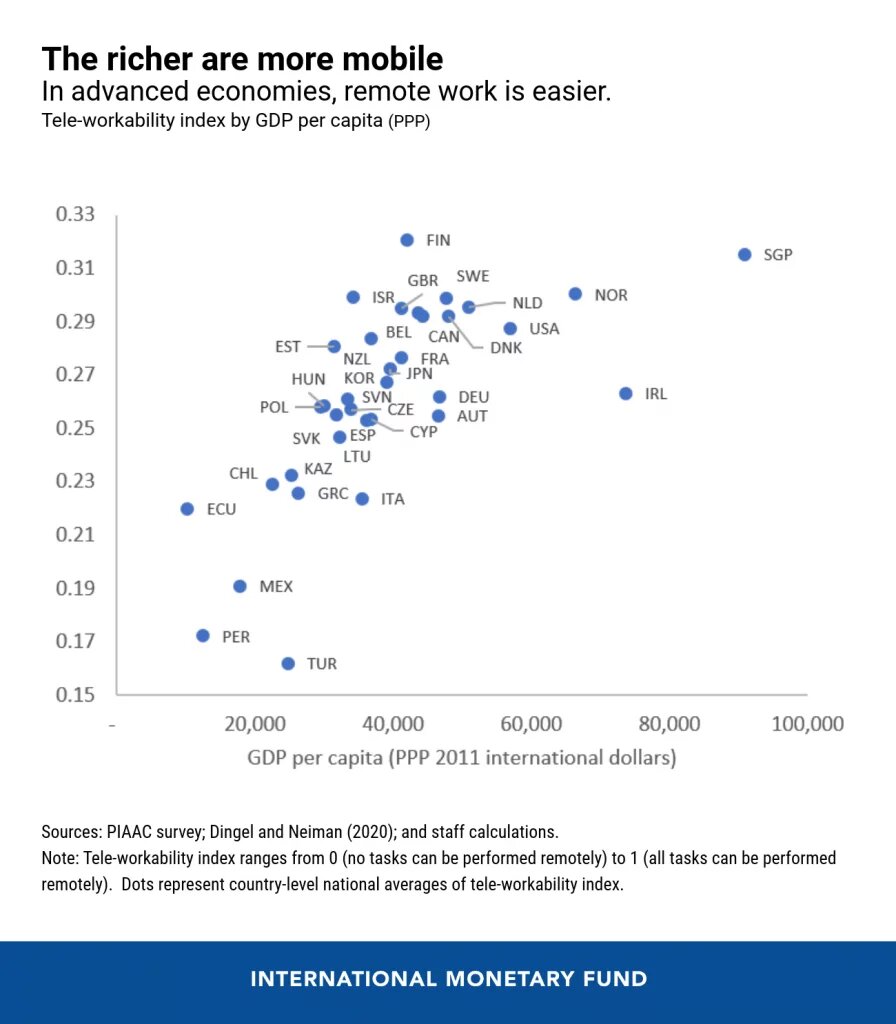

On the other hand, “social distancing” has affected professions and workers who cannot work remotely or using their computer. According to international surveys, those who have borne the brunt of the crisis are those who are less able to cope with it: The poor and young people in poorly paid jobs. An International Monetary Fund (IMF) survey estimates that 15% of workers are at risk because they cannot do their work from home by teleworking. According to this research, although there are differences from country to country or even between professions, it seems that the wealthiest may be more likely to work remotely, and among those most affected are young people, women and informal workers.

However, some social groups are more vulnerable than others, according to the IMF survey:

- Women could be particularly affected, at the risk of undoing the progress made over the last decades on gender equality issues. This is because women work disproportionately more in the sectors most affected, such as entertainment, culture, social care, cleaning, and shop cashiers. In addition, women bear a greater burden of childcare and domestic chores, while the provision of these services in the market has been disrupted.

- Young workers and those without university education are less likely to work remotely. The risk is also linked to the age of those working in the sectors most affected by quarantine and “social distancing” policies. The crisis could also increase inequality between generations.

- Part-time employees and those working in small and medium-sized enterprises face a higher risk of job losses. Part-time employees are often the first to be unemployed when economic conditions deteriorate, as they are now, and the last to be hired when conditions improve. They are also less likely to have access to health care and social security, in order to be able to access measures and support that can help them cope with the crisis, particularly in countries with high rates of uninsured, informal and undeclared work such as Greece. In less developed economies, part-time employees and those working in atypical forms of work face a dramatically higher risk of falling into poverty.

The case for equality concerns the whole of society, not just women

However, gender equality is not just a matter for women, but also for men. It is not just about women but also about a more just, resilient and inclusive society. Inequality is not only to the detriment of women but also of the society that cannot make use of the skills, abilities, knowledge and talents that women may have. Today, many women's potential remains untapped due to significant gender inequalities across the EU. If we want to create a fairer, more resilient, socially cohesive and united Europe, we must eliminate these inequalities.

According to estimates based on research by the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) –the EU organisation that focuses its work exclusively on gender equality– improvements in gender equality could create up to 10.5 million extra jobs by 2050! In 2050, the employment rate would reach almost 80% and EU GDP per capita could grow by almost 10%. Increasing women's employment improves economic well-being for all.

The pandemic awakening to eliminate gender inequalities

The Covid-19 pandemic is of course a major crisis and has serious implications for the health and lives of millions of people, but it is also a call for change, including a wake-up call for gender equality in Europe and in our country. The health crisis has shed more light on everyday social inequalities, including gender inequalities that often go unnoticed: From the multiple presence of women in cleaning or nursing services and their lower presence among medical staff, to the domestic violence faced by many women or the need to take time off work in critical economic sectors to care for their children or people with longstanding problems at home during the pandemic and lockdown.

It will probably still take some time to fully understand the impact of the pandemic and the measures taken on different social groups and different sectors of social and economic activity, as well as on gender equality issues. But it is also clear that, unless there are more targeted actions in recovery plans, there is a great risk that the fragile achievements made over the last twenty years on gender equality issues will be threatened.

Learning from the tools that were used temporarily during the crisis

The effects could have been even worse if some government measures were not already in place in various countries. The UN's Covid-19 Global Gender Response Tracker shows that countries have adopted nearly 1,000 policy measures to address gender-related challenges. These include paid leave for women, labour protection measures, more flexible work and income/in-kind support for vulnerable households or running schools for employees in critical health services such as hospitals. An IMF survey concludes that these measures are working. But the temporary nature of many measures or their premature withdrawal may exacerbate inequalities in the post-Covid period.

More women in green jobs and in the implementation of the green recovery

Now that governments are designing their recovery and resilience programmes, as well as the plans for the Green Deal and the Multiannual Financial Framework 2021-2027, it is necessary to integrate gender dimension in them, as for example Greece, in its “National Recovery and Resilience Plan - Greece 2.0”.

But the Recovery and Resilience Plans and the Green Deal must adopt new tools that integrate gender dimension, not as a general approach –as is the case today– but in a concrete and effective way. The aim must be to contribute to the rapid reduction of gender inequalities and to create a more just society. Two of the tools that can be implemented are the so-called “gender budgeting” that (should) permeate all recovery programmes and the monitoring of results in terms of equality objectives by means of the “Gender Equality Index”.

Given that women are proportionately more sensitive to environmental, climate and social justice issues, more active participation of women in green jobs and in the programmes that will be supported by the Recovery Plan –which should focus on Green Recovery– would give greater impetus to promoting the transition to a more resilient, equitable and green economy.

Improving the participation of women in green professions would also help to increase the proportion of women in specific careers, such as engineers where the ratio of women engineers to men engineers is very low (21% women, 79% men).

How will tools be created to help eliminate inequalities?

Of course, in previous programmes, particularly the so-called NSRF programmes, the gender dimension was theoretically present. Except that it usually ended up being a wishful thinking that those designing programmes knew they had to put gender equality in fine words in the programmes. In practice, however, there were neither indicators of effectiveness nor, more importantly, an evaluation of what worked and what did not work in trying to mainstream gender into the programmes and measures that have been carried out.

In recent years, the “gender budgeting” has been proposed (and now there is growing interest in it) as a tool that can help countries to focus resources on women and ensure that future public (and why not private/corporate) budgets are better on this issue than the previous ones and that they actually achieve the inequality eradication goals they describe in words. The “gender budgeting” can be accompanied by the “Gender Equality Index” used by the European Institute for Gender Equality.

Gender budgeting - a guide

The first step is to design and adopt coherent recovery and green transition policies with the participation of citizens, civil society and the various groups concerned with gender equality. But adopting such policies is only half the battle. Their effects can be further enhanced as part of a coherent gender strategy that is needs-based, effectively designed, aligned with the budget process, and monitored and evaluated to improve its implementation. According to its proponents, the essence of gender budgeting is that it integrates gender into the policies and processes of Public Financial Management and Public Finance, leveraging the powerful tool and resources of “national budgets” to address gender inequalities.

Gender budgeting is an ongoing and long-term investment; it requires building on existing experience of other countries, developing and using a set of measures and actions. It also requires that reliable and continuously updated data are available, such as an assessment of the impact of the pandemic and restrictive measures on women and girls. It is impossible to have effective measures without detailed, quantitative and localised data on the problems. In that way, appropriate policies and measures can be designed with the participation of citizens, especially women and young people who are most affected.

In order to prepare a “gender budgeting”, there needs to be reliable data on how the sectors in which women dominate in the country are evolving, what services women rely on to meet needs such as child education, care for people with chronic problems, what other problems women face, etc.

The United Nations Office for Women (UN-Women) quickly implemented a system of recording in a Gender Needs Assessment document and within just one month, at the beginning of the pandemic, was able to conduct a gender needs assessment in Ukraine based on telephone and online surveys. Similar “Gender Needs Assessments” can identify unwanted gender biases or the effects of implementing a wage subsidy scheme that simply leaves out informal workers (such as women caring for their children or the long-term unemployed) who bear a double burden. Also, an inappropriate tax policy could discourage women from working.

Data-driven policies can be more targeted and effective. This does not mean that, despite the data, the policies designed cannot be misguided or ineffective. To avoid poor policy design, it is important that women beneficiaries are involved in the whole process, from data collection and policy formulation to the assessment of implementation problems or gender impacts of the implementation of policies and measures.

In Austria and Canada, gender impact assessments are now part of all new budget proposals.

Policies must be backed up by a corresponding allocation of resources

The concept of a gender budgeting is based on the realisation that without adequate resources being allocated to gender policies to turn goals into action, policies will remain a wishful thinking. If we want to reduce inequalities, the resources allocated to women must be increased. For example, the IMF programme in Egypt included measures to support higher credit for targeted cash payments to women and improved public childcare services.

As governments prepare recovery budgets –32 billion Euros in Greece– a “gender budgeting” could provide a solid basis for channelling resources for recovery that would also help reduce gender inequality, provide a tool for transparency and confidence-building, and facilitate evaluation of progress and achievement of targets. For example, a specific “gender budgeting” for the “National Recovery and Resilience Plan - Greece 2.0” should incorporate priority policy areas that are important and supportive of women, such as, for example, healthy services that are necessary for women, nutrition for health, mental health support in times of crises and treatment of “trauma” created in periods like the pandemic, women's participation in the circular/green economy, upgrading of digital skills and competencies, social protection etc.

Monitoring and evaluation

Monitoring the performance of budget allocations using “Gender Equality Indicators”, evaluations of results and ongoing dialogue and participation of women in the evaluation process can provide information and suggestions for improvements and changes that may be needed to ensure that policies are working.

Since the start of the pandemic, more than 55 countries have invested in gender budgeting training. Almost all countries have gender equality goals but it seems that only half of them have a legal framework for their implementation and ultimately only a quarter of these countries use established practices such as Gender Budget Statements and Gender Impact Assessments. Some countries have already implemented gender budgeting, and these too have room for improvement. Many others, however, have not even designed such a model, much less formulated one through participatory planning, in collaboration with the women and organisations concerned.