This article focuses on buildings' energy efficiency, the national commitments in the context of the European strategy and the climate and social related benefits from an effective energy efficiency policy.

One of the basic pillars of Green Deal and Europe's new climate target of 55% greenhouse gas reduction until 2030 is the energy saving in all fields of EU Member States’ economy. European Commission’s latest report on energy efficiency targets (20% reduction in energy consumption by 2020 compared to 2007) shows the Member States’ great deviation from the 2020 targets (4%-6% per year). COVID-19 crisis reduced temporarily the energy demand (International Energy Agency showed that every month of full lockdown leads to 1.5% reduction of demand on an annual basis) but it did not make any structural changes. So, without specific policies, the expected financial recovery will bring the energy demand back at the pre-COVID-19 period.

Based on “Directive (EU) 2018/2002 on energy efficiency” the relevant target of Member States is set at 32,5% by 2030. Given the current results that have felt behind on the 2020 measures, the distance from the energy efficiency targets for 2030 is greater (around 22% in primary and 17% in final energy consumption). In Commission’s assessment of National Energy and Climate plans (NECPs), it was shown that, despite the initial aspirations expressed by Member States, there is an overall gap in national contributions concerning the 2021-2030 targets. According to the new climate targets, we must achieve at least 39%-41% reduction of primary and 36%-37% of final energy consumption.

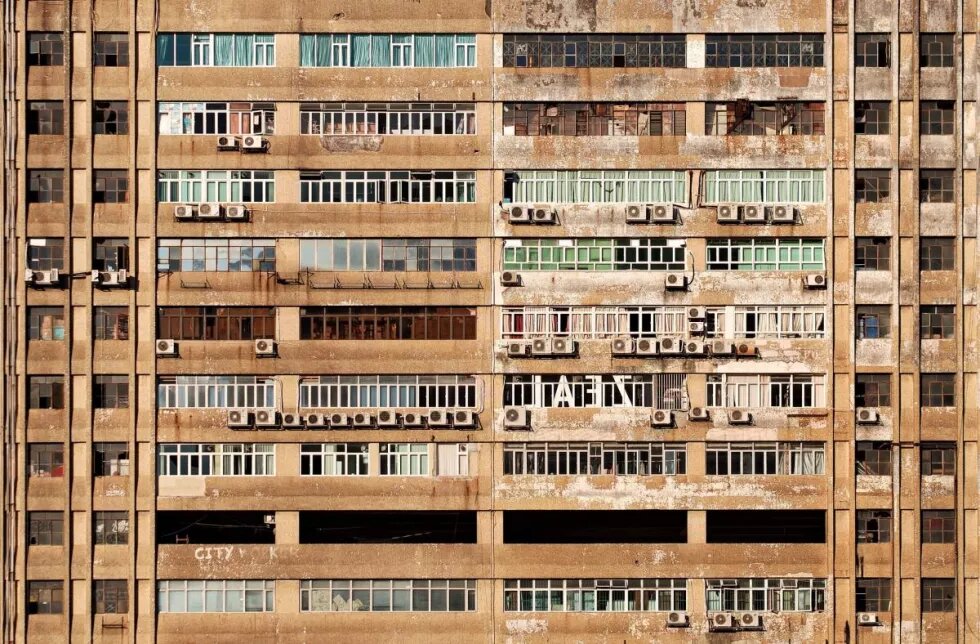

So, energy efficiency must be at the centre of policy-making by estimating, on fair bases, which energy supply and demand investments are the most efficient when the cost on society and economy is measured. In this context, the European Commission has set the “Energy Efficiency First” principle, as the cornerstone of NECPs. It is also an important element of the “Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 on the Governance of the Energy Union and Climate Action”. This principle is fundamental for policy-making, planning and investing in the energy field; European Union’s energy system should be designed based on it. According to this principle, investments in energy demand that lead to energy saving (such as upgrading buildings’ energy-efficiency) should come before any classic investment in energy supply (such as expansion or construction of new networks) as the former are more cost-effective after adding their social benefit in the equation, meaning, the multiple benefits of energy saving for the its user.

The dilemma about whether to finance transnational gas pipeline connections or district heating expansions, or, alternatively, to fund building upgrades (based on Renovation Wave) or energy-efficient heating systems should always be answered during the decision-making process. Also, any costs, future investment risks and multiple benefits should be calculated separately. Energy efficiency and energy demand management are both key elements of the energy system and they should be treated on equal terms with energy supply.

When we examine whether the “Energy Efficiency First” principle is applied in Greek NECP, we see that Greece, among other countries, has not taken it into sufficient account while aiming for investments:

- In natural gas import and network expansion which, due to their size and duration, can lead to lock-in situations (e.g. on natural gas supply), making the energy transition difficult. And, in 20 years, they can create 30,000-40,000 € per household transition cost (as the example of cities in the Netherlands shows).

- In search for fossil fuels with significant investment costs.

As the discussions of Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) of the EU and the decision of European Investment Bank (EIB) about funding alternative fuel investments revealed, these investments also cause serious funding difficulties on a transnational level.

If we compare the estimated investment needs for these actions (delignification, gas, etc.), the expected funds are three times the ones related to energy savings (which are expected to reach 11 billion euros, with public funding of 3.5 billion euros for the period 2021-2030).

In the private sector, based on a study by EIB, 1/3 of the companies that invest in Greece, also invest in energy efficiency (26% of all companies). In Greece, companies spend almost 1/10 of their overall investments in energy efficiency improvement, which is a much smaller percentage than the average in EU and USA.

Under the “Energy Efficiency First” principal, Greece's target on new energy savings is 0.8% per year for 2021-2030, that is, 7.3 Mtoe cumulative energy savings based on average consumption in 2016-2018. Being 30 times higher compared to the one of the current period means that the corresponding policy measures should overmultiply the savings (with proportional funding needs).

When it comes to the new Saving-Autonomy program (with initial funding of 900 million euros), according to NECP, all residence energy upgrade programs should yield 52 ktoe new annual savings (2,878 ktoe cumulative savings in 2030). As a measure of comparison, the respective Saving at Home I and II programs aimed at just 251 ktoe cumulative energy savings by 2020. So, basically, the new program must reach twelve times the potential of Saving at Home I and II.

It is therefore necessary for Greece, if it really wants to achieve its targets, to proceed with much more actions and measures. The current plans for the future, such as the recent delignification master plan where energy savings are mentioned as a supportive action in a 430-page text, as well as other plans being discussed (e.g. European Commission “Recovery Facility”) do not attach the sufficient importance to energy savings.

When it comes to employment, the social aspect of Green Deal should also be taken into consideration, as for every million euros invested there are:

– about 18 local and long-term job openings in building energy renovation sector in Europe.

– just 5 job openings in fossil fuel industry.

At the same time, for every 10 million euros spent there are:

– 75 job openings in Renewable Energy Sources, directly or indirectly,

– 77 job openings in energy efficiency activities (buildings, transportation, smart networks etc.) and

– just 27 job openings in fossil fuel industry (oil, lignite and natural gas).

In Europe, energy savings created 964,000 new job openings (in 2017) with an increase of 17.4%, while the GDP was rising by 0.5%

So, if we take into account the expected funding, the set targets, and possibly the arguments for increasing employment by investing in specific energy sources (such as hydrocarbon extraction and gas infrastructure), these do not seem to be entirely in line with reality.

Any investment that will determine our energy future should be co-formed by consumers in one side and producers and distributors of energy in the other while respecting the ‘Energy Efficiency First’ principle, in order to be acceptable in national and European level and socially and economically efficient when their evaluation comes.

Given the set targets, it is an opportunity to carefully examine the alternatives and design a truly viable energy transition. We should not forget that energy saving is the economy's primary fuel and Greece has a great potential that can be used as driving force of its economy!