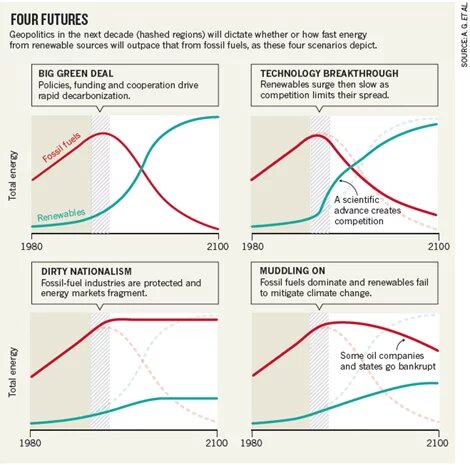

When I arrived in Berlin in August 2018, it was impossible to guess how different the world we are living in today would look compared to the summer four years ago. I had just started to work as a research assistant at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs – Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP) in a project called the “Geopolitics of the Global Energy Transformation”. Building on two scenario workshops and deep-dive discussions with experts from all over the world, the key motivation back then was to better understand where the moving target of the global energy transformation is getting us and what geopolitics have to do with it. This resulted in four different scenarios published in a seminal Nature article in May 2019 with starkly contrasting realities. The point was not to exercise sophisticated crystal ball gazing, but rather to reflect on a deeper, more structural level, and paint the energy world of the future (2030) on a decidedly geopolitical canvas.

Dirty nationalism – currently a very popular contender

Looking at the article again in October 2022, there seems to be a peculiar resemblance to one of the scenarios (see figure below, bottom left) which at the time struck me as rather bleak: dirty nationalism.

The Nature article was published in the middle of the Republican-led presidency under Donald J. Trump (2016-2020), at a time where the campaign slogan “America First” had long become substantiated in concrete industrial and energy policies. In 2017, U.S. President Trump had proudly announced that he would withdraw the U.S. from the Paris Agreement, and “freedom gas” – U.S. liquefied natural gas (LNG) shipments to Germany and the EU – was the talk of town in the autumn of 2018. In fact, then U.S. Deputy Secretary of Energy Dan Brouillette had come to Berlin to promote U.S. LNG exports during meetings with German political and industrial elites – and paid a visit to the SWP as well.

The first paragraph describing the dirty nationalism scenario’s implications starts as follows:

“Elections bring populists to power in the world’s largest democracies, and nationalism grows. Nation-first policies put a premium on self-sufficiency, favouring domestic energy sources over imported ones. This drives the development of fossil fuels, including coal and shale production, as well as renewables.”

Meanwhile in Brazil, the far-right populist president Jair Bolsonaro had begun to dramatically accelerate the large-scale deforestation of the Amazon to unprecedented levels. The feedback loops between sustained deforestation and wildfires in the Brazilian rainforest drove carbon emissions through the roof amidst worsening global warming. In 2021, a study revealed that the Amazon’s wildfires were producing roughly three times more CO2 than the remaining forest was able to absorb. Ignoring international outcry over the devastating climate effects of his policies, Bolsonaro conducted a nationalist agenda driven by commercial exploitation of domestic resources and the attempt to assuage vested agribusiness interests.

When in doubt, put your own nation first

Fast forward to 2022, where the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) signed into law by Democrat President Joe Biden in August, reveals a different, yet strangely familiar focus of U.S. climate and energy policy: even though not stated explicitly, “America First” is still looming large in the IRA. As much as it is clearly an important financial boost and political lever for American renewables, electric vehicles and other clean tech businesses, the IRA’s objectives are not limited to accelerating the energy transition. Unleashing billions of dollars of tax benefits for U.S. clean tech firms and supporting offshore oil and gas leasing is also a powerful move to ramp up domestic manufacturing and increase U.S. energy security by reducing its dependence on foreign supply chains and critical minerals exports. Meanwhile, the crucial role of U.S. LNG exports to the EU (“freedom gas”) can now hardly be overestimated. In the first half of 2022, 64% percent of its total LNG shipments were directed to the EU and the UK, making the U.S. the biggest LNG exporter in the world.

The 2019 Nature article continues…

“States ring-fence their industries and zero-sum logic returns — one country’s gain means another’s loss. Public opinion turns against foreign energy investors. Energy markets fragment in the face of protectionism, which limits economies of scale and slows progress towards decarbonization. Fossil-fuel exporters rush to produce as much as they can, despite falling prices and constraints on trade.”

Back on the other site of the Atlantic, Italy’s Giorgia Meloni, leader of the far-right Brothers of Italy party won the country’s recent national parliamentary elections in September and is now poised to govern the EU’s third biggest state and economy. But the latter is struggling with skyrocketing energy prices for households, domestic industries remaining dependent on ever-more expensive gas supplies and spiralling national deficits accrued by pandemic recovery spending. Italy is facing massive economic and political challenges in a highly volatile context of equally self-centred EU neighbours. Maybe this explains why its leaders openly criticised Germany for announcing a 200 billion EUR relief package addressed to German households and businesses as a remedy for the continuing energy price crisis. The chorus of EU leaders blaming Germany of abusing its economic clout leading to market distortions was joined by France’s Finance and Economy Minister Bruno Le Maire, Italy’s and France’s respective EU commissioners and Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. Spain’s Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez also issued a cautious warning during a recent joint German-Spanish consultation, even though the rest of the meeting reflected a more cooperative agenda.

Trying to navigate through the dire straits of a multi-layered polycrisis – pandemic recovery, Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, high inflation – European nations seem to be converging toward a common approach: focussing on themselves first.

Military invasion, inflation and an extended subsidy race: dirty nationalism as the recipe for disaster?

Over the last year, virtually every EU Member State has put to use billions of euros of national macroeconomic or fiscal measures to mitigate the effects of the energy price crisis in the period between September 2021 and September of this year. As this comprehensive analysis by Brussels-based think tank Bruegel shows, the measures include reducing energy taxes or VAT on energy, capping national energy retail prices, payments to vulnerable groups, business support schemes and windfall profit taxes, among other initiatives.

The measures all amount to state aid in one form or another; many of them had to be approved by the European Commission’s Directorate-General for competition. In other words: the EU is already finding itself in the middle of a subsidy race for low-cost electricity and access to other forms of “cheap” energy. And much like the misnomer IRA, these European measures are actually susceptible to further fuelling inflation rather than effectively curbing it, insofar as they encourage demand and flush markets with fresh cash. Against the backdrop of central banks increasing interest rates and generally high up-front costs, this in return will make it much harder to finance the much-needed transition to renewables in the short to medium term.

As a matter of fact, not everything happening in the EU’s energy geopolitical arena since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February can be attributed to nationalist regression. The EU passed legislation in unprecedented speed to assure Member States would fill their gas storages and encouraged a joint gas purchasing scheme; several rounds of comprehensive sanctions have been adopted and implemented. What is more, the European Green Deal’s key energy legislative files – the Renewable Energy Directive and the Energy Efficiency Directive – are due for more ambitious revisions and currently in trilogue discussions between EU institutions.

Ultimately, in the context of Russia’s war of aggression, European states are under enormous pressure to deliver quick solutions on a massive scale and on multiple fronts. The slow, complex and often cumbersome EU negotiations to find common ground push its Member States to develop own, national alternatives which might be easier to implement, but more difficult to align with neighbours. It remains to be seen whether dirty nationalism is rather the preferred short- to mid-term tactic to face a geopolitical and economic crisis caused by a war (Europe – Russia) or a rivalling great power (U.S. – China), or whether it becomes the dominant strategy for the years to come.