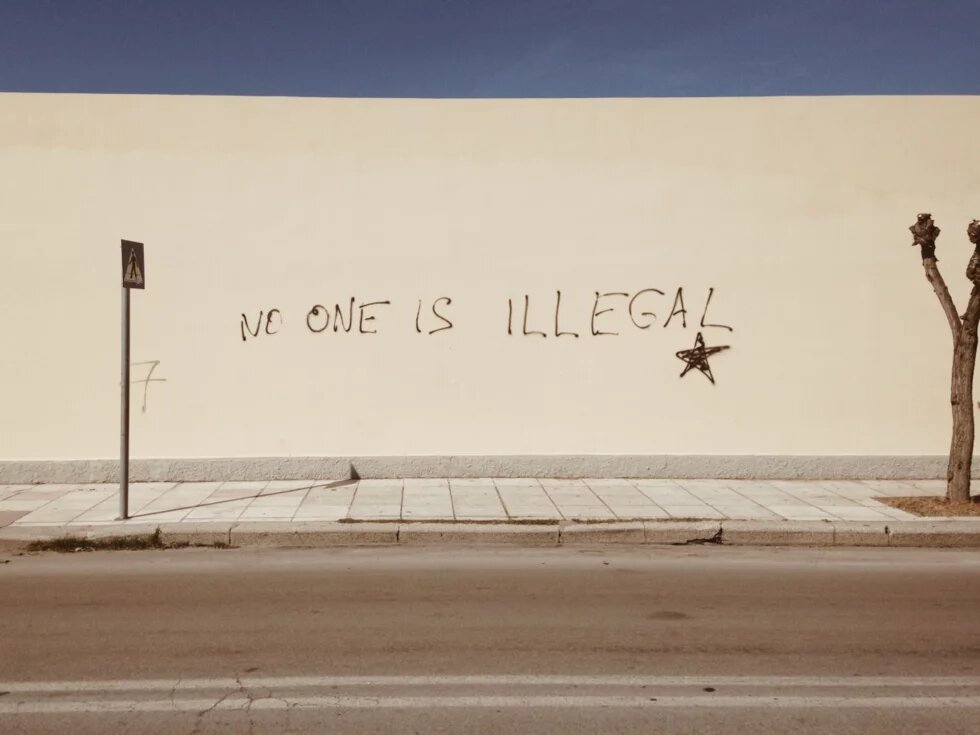

Civil society players have been working hard for years to safeguard the fundamental rights of people seeking asylum in Europe. This has made them the target of an aggressive policy of deterrence, endangering both refugees and solidarity work itself.

Immediately upon my arrival on the Greek island of Lesbos, I and four others were led by police officers for identity checks in a container on the other side of the ferry port. The selection does not seem a matter of chance: we have all come from the island of Samos, where the first of the five new “closed controlled access centres” for asylum seekers has been opened. Even on the walk to the container and for the entire 40 minutes it takes to search our bodies, luggage and notebooks thoroughly, we are repeatedly asked the same question in suspicious tones: “are you NGO?” The same question is constantly – and increasingly aggressively – repeated, as if we have something to hide. Finally, once the police have wrung from us a half-hearted promise not to take any photographs on this popular tourist island, we are allowed to go.

This may be just one example, but it illustrates the generally antagonistic atmosphere I encountered in many forms during my research trip along the Greek-Turkish border for several weeks. This kind of everyday intimidation is just part of the increasingly menacing environment to which People of Colour, migrants, journalists and staff of non-government organisations (NGOs) are exposed. They must also contend with substantial consequences under criminal law, defamation and the tightening up of laws restricting, or preventing altogether, humanitarian, journalistic and solidarity work in the fields of migration and flight. The most fundamental principles of the rule of law are now at stake.

Ever since people seeking protection began arriving in Greece in their thousands every day in 2015, it was non-state players, organisations and dedicated individuals who stood in for or propped up the overwhelmed state structures. They provided an overview of often confusing developments and a window into opaque state measures, carried out education work on the terrible humanitarian conditions for refugees and supplied the most basic infrastructure, such as shelter, education, legal, medical and psychological assistance as well as supplies of water and food. These people set out every day to defend “Europe’s self-image” as a society founded on human rights and the rule of law. At the same time, they have been coming under increased pressure for many years and across the whole of Europe. In Greece, this has been even more the case since the right-wing Conservative party Nea Demokratia came to government towards the end of 2019.

Restrictions on non-government organisations

As part of wide-ranging reforms of asylum policy, Nea Demokratia introduced a new registration procedure for NGOs active in the fields of “Asylum, migration and social cohesion” in February 2020. In the name of the public interest, the reform claims to guarantee “transparency, the optimisation of services” and the “human rights of refugees, asylum seekers and immigrants on Greek soil”.

Every NGO active in the country has had to reregister under the new procedure. On Lesbos, Doro Blancke, head of the refugee assistance charity bearing her name, tells of the problems the new registration procedure has caused humanitarian organisations. She describes the procedure as “ridiculously expensive. The first entry alone costs 9000 euros, in total it’s 25,000 euros and even then, it’s not certain that it will go through!” Liza Papadimitriou of Médicines sans Frontières can also confirm that it is the small organisations that are having to jump through disproportionate hoops and that “these restrictions make it impossible for civil society to go about their work”.

Meanwhile, three different UN Special Rapporteurs – on the right to peaceful assembly, the situation of human rights defenders and the human rights of migrants – have criticised the “onerous” and “hampering” conditions of the new procedure. These reports followed two by the Expert Council on NGO Law of the Council of Europe, dated July 2020 and November 2020, and criticism set out in the rule of law reports of the European Commission for 2020 und 2021. And in May 2021, the Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe, Dunja Mijatović, called upon the Greek government to “build on the recommendations issued by these bodies in order to actively create and maintain an enabling legal framework and a political and public environment conducive to the existence and functioning of civil society organisations”.

All these reports question whether the new requirements are compatible with European legal standards since, amongst other things, they constitute a threat to the right of assembly. The individual information obligations breach data protection and personal rights and some organisations have had their applications rejected for a range of non-transparent reasons. In the estimation of the European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE), the competent special secretariat’s decision-making is not subject to any independent accountability body that could provide effective remedy.

For newer NGOs in particular, one of the greatest obstacles is the requirement to submit extensive financial reports that must demonstrate at least two years’ work in humanitarian fields. While many organisations fall at this hurdle, investigative research by Solomon and Inside Story suggest that there could be irregularities and double standards in the registration procedure. In early 2020, an NGO with ties to the government that had long been inactive was transferred to the brand-new organisation Hopeland. One week after its creation, Hopeland answered a call for tenders of the ESTIA II programme even before it had been listed in the public register, received the first €500,000 of an estimated total of €6.5 million in EU funding. In response to questioning from Solomon reporters about this unusually straightforward and speedy procedure, the management’s answers contained many contradictions. The Ministry for Migration declined to comment. While government members regularly attempt to discredit organisations for “wasting money” and “manipulating refugees”, as Solomon reports, the Ministry clearly has no problem awarding “contracts worth millions to questionable NGOs, sometimes even bypassing the conditions that were set by the government itself”.

In March 2021, the legal support and partner of “Pro Asyl”, Refugee Support Aegean, described the new NGO register as “disproportionate” and “discriminatory”. In December of the same year, the Greek authorities rejected its registration application. The reason given for the decision was that the “development of activity in support of persons under deportation” runs counter to Greek legislation. Yet the European Convention on Human Rights explicitly covers work of this kind and many other organisations registered in Greece are active in this very field.

In view of this development, the Expert Council on NGO Law of the Council of Europe came to the conclusion that the new provisions do the opposite of what they promise: rather than optimising services, NGOs’ work has been made disproportionately harder; instead of protecting the rights of refugees, their access to the organisations that protect their rights has been withdrawn and instead of promoting greater transparency, it has created a forum for arbitrary decisions.

Xenophobic discourse and the defamation of solidarity work

“Protecting the blood is the only way to protect Greek society […]. There can be no border protection without losses. More specifically, without deaths. Border protection needs deaths. Islam is coming and it will bring down the whole of Europe, including Greece. The aim is therefore to obstruct their future […]. Their previous life should seem like paradise compared to their life here. That is the only way we will stop them coming”.

Thanos Plevris said this in 2013, addressing a group of like-minded individuals, before he took the position of Minister for Health in 2021. He is currently responsible for health care provision for all asylum seekers in the country. Along with Minister for Migration Notis Mitarakis, he represents the far-right wing of Nea Demokratia and Plevris’ racist and anti-Semitic comments illustrate the aggressive, inflammatory tone that has become acceptable in government circles.

The government is following a rhetorical line that increasingly portrays refugees as “illegal migrants”. NGOs, accordingly, are variously portrayed as part of a corrupt humanitarian industry, manipulators of refugees or the extended arm of international human trafficking.

The current media landscape in Greece is tailor-made to support this strategy (article in German only). The strong ownership concentration in the media sector as well as the direct control exerted by the Prime Minister over the public broadcasting service ERT and the state news agency ANA-MPA are a threat to balanced, diverse reporting.

In addition there is the serious intimidation of journalists and independent observers, such as secret service investigations against the aforementioned investigative magazine Solomon or the expulsion of the ASGI observation mission staff by police and Frontex officials. In particular, the security zone on the border with Turkey in the Evros region is considered a “black hole” for independent observers – the very place where most of the pushbacks documented in recent years have taken place.

It therefore comes as no surprise to learn that Greece takes just 70th place in a freedom of press classification carried out Reporter ohne Grenzen. The Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom describes the political independence of the media in Greece as being at a high risk, the same rating as Turkey and Hungary.

Criminalising refugees

In parallel to the political and media discourse, in which refugees and any form of solidarity with them is problematic and a threat to Greek sovereignty, there has been a wave of criminal prosecutions with serious consequences.

The authorities have taken a particularly tough stance against refugees themselves, who have little media publicity and little material support to defend their fundamental rights. While legal proceedings, including those against lifeguards Sean Binder and Sarah Mardini (article in German only), have had met with considerable – albeit too little – public interest, the criminalisation of many refugees continues largely unnoticed. The trials against the “Moria 35”, the “Moria 10”, the “Moria 6”, the “15” and the “Samos 2” are just a handful of examples of legal action being taken against refugees.

In April 2021, a young Syrian man, known as K.S., was sentenced to 52 years’ imprisonment for illegal entry and smuggling, because, according to the prosecution, he was steering the dinghy in which he, his wife and their three children reached the island of Chios. In May 2021, sentence was passed on Lesbos against a 27-year-old Somali man, Mohammed H., condemning him to 142 years in prison on similar charges and his alleged responsibility for the death by drowning of two women.

In the current proceedings against the “Samos 2” (article in German only), the potential sentences could also stretch into decades: Ayoubi Nadir from Afghanistan foundered against cliffs on the island of Samos in stormy seas, along with his six-year-old son Yahya and 22 other passengers. His son tragically drowned. Nadir and one other survivor named Hasan were arrested. Nadir faces 10 years’ imprisonment on the grounds of “child endangerment” – the death of his own son – and Hasan life imprisonment plus 230 years for “prohibited transport”.

Both of these cases refer to an EU directive of 2011, setting out a minimum prison term of 10 years for people smuggling, for having “by gross negligence endangered the life of the victim”. An additional EU initiative came along in 2015, stipulating that the criminal act of people smuggling could be deemed to exist even without a “profit motive”. Since it is rarely the smugglers themselves at the helm of the vessels, these EU laws make it easier to bring targeted proceedings against refugees themselves.

Furthermore, procedural irregularities disregarding the fundamental right to justice are common currency in Greece. Court observers and legal assistance organisations such as the Legal Centre Lesvos have reported on many cases in which the defendant had no mother tongue interpreter present. Another recurring theme is that the chief witnesses for the prosecution are either police officers or were not personally present and cannot therefore be questioned by the defence. Exonerating statements by defence witnesses frequently go unheard or are overlooked in the judgments.

Pushbacks, fake news and the restriction of sea rescue missions

As Greek Prime Minister Mitsotakis made clear at a controversial press conference in November 2021, the Greek government – and Frontex – are sticking doggedly to the story that there is no material evidence of any pushbacks. Rather, reports of violent repatriations are dismissed as “fake news” or “a Turkish conspiracy”.

Yet there is no doubt that the Greek authorities have been carrying out pushbacks on the border between Turkey and Greece for decades. Since March 2020 the extent of this practice has reached new levels of brutality and efficiency, with refugees picked up as soon as they reach Greek soil, taken in a group to a secret location or police station, often mistreated and stripped and then abandoned near the border. Many people die in this process, but only a handful of these deaths are documented. According to Hope Barker of the Border Violence Monitoring Network, 2020 saw “87 pushbacks from Greece to Turkey concerning 4683 people. Since the beginning of 2021, we have received 54 witness statements corresponding to approximately 4007 people. And that is only what we have documented”.

In November 2021, the government nonetheless stepped up its clampdown on fake news. A further tightening-up of criminal law now criminalises the dissemination of fake news that is “capable of causing concern or fear to the public or shattering public confidence in the national economy, the country’s defence capacity or public health”.

Anybody breaching these vague stipulations faces six months’ imprisonment. Eva Cossé of Human Rights Watch in Greece sums up the situation: "In Greece, you now risk jail for speaking out on important issues of public interest, if the government claims it’s false”.

The government took a further step in its recent amendment of article 40 of the “Deportation Law”. This move paves the way for serious consequences under criminal law for independent observers and volunteers in the Aegean active in sea rescue missions or monitoring pushbacks. As well as being subject to a new registration obligation, participating organisations are only allowed to carry out rescue operations once they have received explicit permission to do so from the coast guard. Organisations such as Mare Liberum, the only international monitoring mission present in the Aegean, now face the dual challenge of having to be registered by a government authority that denies the existence of pushbacks and of having to comply with the orders of a coastguard that carries out pushbacks. To make matters worse, the coastguard carries responsibility not only for the waters, but also for sections of the coast, meaning that assistance to refugees having made landfall now comes under the stringent measures of the new law.

These tighter new legal provisions are flanked by the public announcement of police and secret service investigations into Mare Liberum and members of three other NGOs plus six “third-country nationals” (article in Greek only) accused of “espionage” and “assisting illegal entry”. The unusual step of making these investigations publicly known even before any criminal proceedings have been set in train suggests that there is no concrete evidence. Even so, these investigations have a deterrent effect that should not be underestimated.

Europe of despotism or Europe of solidarity?

All in all, this has created an increasingly tightly-woven web of legal measures, opaque procedures, threats of criminal action and serious intimidation that are putting the squeeze on solidarity work, independent reporting and the ability of refugees to rely on their fundamental rights. The party currently in government and sections of the judiciary seem to be pulling out all the stops to solve the “problem of illegal migration” and the provision of assistance to refugees out of solidarity – very much chiming with the interests of EU asylum policy, which at the least tolerates this constantly escalating arbitrary treatment and violence against people in search of protection on its own borders. The new German government must use the leverage of its “new start” to tackle the strategy of deterrence on the EU external borders head on and not to minimise it as a “necessary evil”. Their commitment is needed to defend those who make the difference every day between a Europe of despotism and a Europe of solidarity.

This article was first published in German on boell.de.