Whilst the national governments have been reflexively ducking responsibility for years, there are many cities in Europe, from London to Munich and Vienna to Lille, Barcelona and Lisbon, that are expressing solidarity and a readiness to take in refugees.

Recent weeks have once again made it painfully clear that the EU’s refugee and asylum policy is hobbled by a knee-jerk national policy and discourse of building barriers and that there is no coordinated and effective human rights-based policy.

This was made particularly clear by the reactions to the power-grab of the Taliban in Afghanistan and the ensuing debate on how to cope with refugees in Europe. In many places, this debate was restricted to a rhetoric of fortification and an insistence that “there must be no repeat of 2015”. It is particularly worth noting that the discourse shifted towards the political centre not just in the capitals, but also in Brussels.

The current situation on the eastern borders of the EU and dealings with the refugees in the Baltics and Poland being used as pawns by Belarus shows that there is a lot of support in the EU capitals for this fortification reaction, including illegal pushbacks. Minister President of Saxony Kretschmer has called for “fences and walls” on the boundary with Belarus and German Home Affairs Minister Horst Seehofer mooted the idea that the EU could provide Poland with financial support for the construction of this kind of “fixed border installation”.

No improvement is in sight and the “New Pact on Migration and Asylum” proposed by the European Commission in autumn 2020 takes us further down the road we first struck in 2015: outsourcing responsibilities to third countries, focusing on returns, classifying migration and flight as a management and security issue and flouting applicable fundamental human rights.

Cities and communities provide a glimmer of hope

But while national governments have responded for years by ducking their responsibilities, there are many cities in Europe, from London to Munich and Vienna to Lille, Barcelona and Lisbon, that are expressing solidarity and a readiness to take in refugees. In stark contrast to statements made by his country’s head of government, for example, Michael Ludwig, Mayor of Austria’s capital city of Vienna, has called for more solidarity and urged the federal government to provide a safe haven for people from Afghanistan seeking protection: “in any event, Vienna is ready to welcome these people to our city, which is not called a human rights city for nothing”.

Even if the statements of welcome made by individual communities concerning concrete reception pledges for a couple of hundred places each are largely symbolic, they are an important signal being sent out by these local governments. Right across the European continent – from Barcelona to Bergamo and onwards to Bonn – we are seeing signs of solidarity and humanity. This readiness to take responsibility instead of looking the other way bears testimony to an attitude that is, in many cases, diametrically opposed to that of the national government.

Taking cities’ and communities’ offers seriously and making use of them

As the community level is the very one that is responsible for the long-term hosting and integration of refugees, these offers are not empty gestures, but both credible and relevant. They indicate that many cities and communities are prepared to embrace a culture of welcome in the framework of a coordinated, human rights-based EU asylum policy.

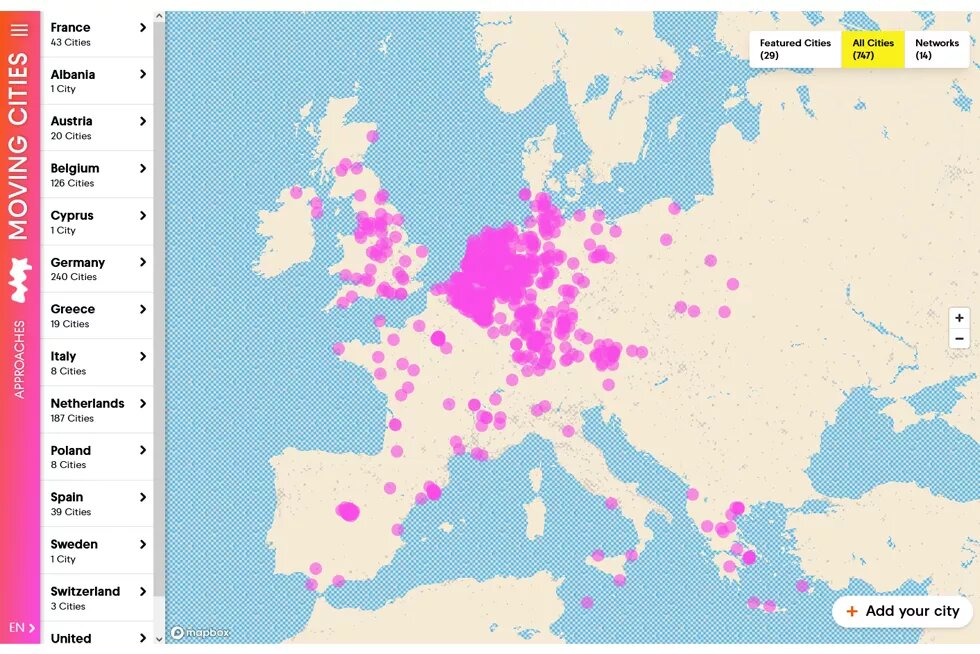

Many of these are already providing a daily masterclass in what good hosting and the integration of asylum seekers can look like. There are already many pioneering cities working in alliance with a broad civil-society base of support organisations and helpers showing how success in the hosting of migrants can be achieved and serving as an example. Recently, this has been underpinned by a website launched by Seebrücke, the Rosa-Luxemburg Foundation and the Heinrich Böll Foundation, called Moving Cities. It is therefore critically important to start taking the offers made by cities and communities seriously and make use of this positive energy.

Cities and communities with open arms vs. unwelcoming national governments

But how will it work if cities are more prepared to receive than national governments? There is still no legal framework for this. In Germany, for instance, cities are “bound by the current legal situation by decisions taken at federal state and national level, although they are free to try and influence these with their political weight. It is not until migrants arrive, when communities become responsible for their accommodation, support and integration, that the focus of responsibility moves to the community level, with the decision-making freedom that entails”.

Communities are not able to take refugees in voluntarily until they have been allowed to enter the country by a state decision. Communities are currently permitted no autonomous involvement in refugee admissions and the legal question as to what leeway cities and communities also have in Germany’s federal system has not been conclusively answered.

More say for cities and communities

What this boils down to, therefore, is that communities should be given the opportunity to take more asylum seekers over and above the quota allocated to them by the national or regional authorities. For this to work, the communities would have to have more say and there would have to be more direct communication channels between the community and European level. The question has financial dimensions as well as legal ones.

Proposals for the legal position of communities to be bolstered are already on the table. Specifically, for instance, the creation of a new “type of visa for community admissions”, whereby a person would be able to apply for asylum or entry on humanitarian grounds directly in a given community. In the framework of a visa procedure of this kind, “communities could issue their (prior) approval and cost absorption declarations for the admission of certain persons”, according to an expert legal report. Another option would be to make article 23, paragraph 1 of the German Residence Act into a code of conduct, so that the federal states would no longer have to seek the approval of the Federal Home Affairs Ministry before setting up humanitarian reception programmes. This system would also require a European arbitration body that could intervene in the event of conflict between communities and national government.

There is also the question of giving communities a financial shot in the arm by means of simplified access to EU funds (e.g. AMIF and ERDF) and more of a voice in the distribution of EU resources to smaller or poorer communities. Money is a key factor in realistically implementing an appropriate reception and integration policy for asylum seekers. Without it, communities’ hands are tied. Communities should therefore be able to apply directly for flexible emergency aid from the EU, especially for emergency support from the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund, without having to go through the nation state. This would allow needs to be covered quickly and without unnecessary complications. The financial support of communities would not just help the communities that are already prepared to take refugees, but would also motivate new regions and communities to add their efforts.

Whether, and where, sufficient local admission places are available should be based on capacities and opportunities: where is there affordable accommodation? Where is there a shortage of labour? Where are there civil-society networks and community structures? In addition to quotas, a matching system between the communities and individual refugees and asylum seekers could create a new dimension of differentiation, creating a win-win situation for all involved.

If not everybody wishes to join in, those who do should go on ahead

Recent weeks have shown once again that a new direction for EU refugee policy is urgently needed. Many cities are now speaking up to declare their willingness to host, are coming together in city networks to give themselves more of a voice. They should now be listened to and given more of a say. The new German government should tackle this question and advocate for the necessary legal framework at national and EU level.

If this urgently needed reform cannot be implemented with all EU member states, those that are willing to host must have the courage to go on ahead. It is likely that to begin with, progress will be possible only by means of enhanced cooperation between the member states that are not prepared to wait any longer and which support a coherent EU refugee and asylum policy. These countries should wait no longer and break new ground that is worthy of a European Union of values – in the hope that the other countries will follow.

This article was first published in German on boell.de.