On September 23, 2019, from the podium of United Nations, the Greek Prime Minister announced the decision concerning the country’s full independence from lignite by 2028. It is a milestone decision in the history of Greece’s energy policy as the lignite has been the dominant fuel of the country’s energy mix for many decades.

Few months later, the decision was specified and included in the new PPC (Public Power Corporation) business plan and in the National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP). Both of them include the same timeline of closing all the existing lignite-fired power plants by 2023 except the under construction plant Ptolemaida 5 that will continue generating power from lignite from 2023 to 2028. Its installation started in 2015 with a total cost of 1.4 billion euros. Ptolemaida 5 is planned to start functioning in 2022 or in 2023 while there is no information regarding its future after 2028.

The lignite production through the years

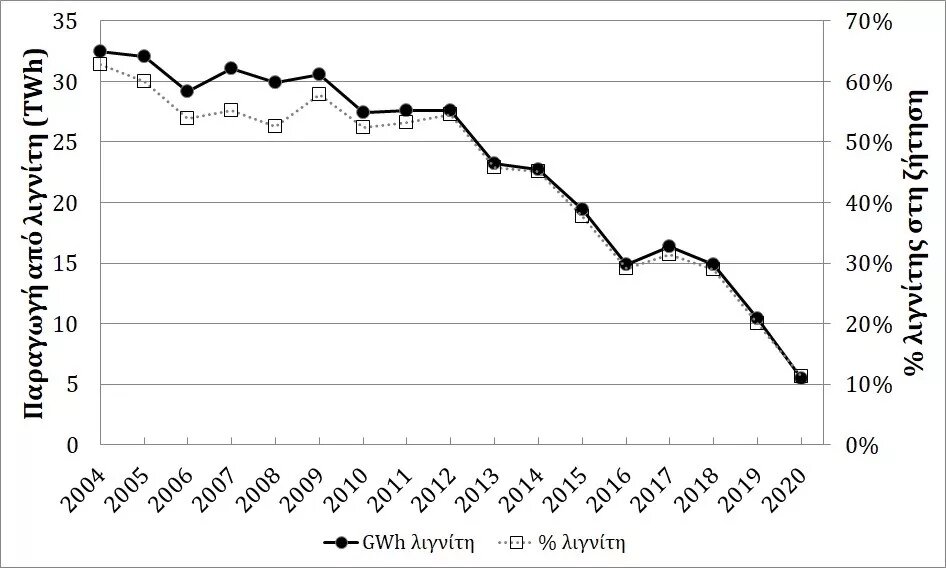

The lignite phase-out was not initiated by the Prime Minister’s announcement. As it is shown in Chart 1, based on the official data of The Independent Power Transmission Operator (IPTO), starting back in 2004 and until today, the contribution of lignite to the country’s electricity production mix is being reduced almost every year and so is its corresponding share in demand coverage. It is notable that over the last decade the lignite power generation decreased from 27.4 TWh in 2010 (63% of the demand)to 10.4 TWh in 2019 (20% of the demand).

*For 2020, according to the estimation of the President of PPC, it is predicted that lignite electricity production will not exceed 5.5 TWh. The total demand for 2020 is estimated to be 6% lower than the one for 2019.

It is absolutely certain that the historically low record of 2019 will be broken in 2020 as in the first ten months of 2020 there is an overall reduction of 50,6% in lignite electricity production compared to the same period in 2019. The monthly reductions in 2020 in comparison to the corresponding ones of 2019 are from 15% (in February) to more than 75% (in June) (Chart 2).

From the 7th of June to the 9th 2020, for 39 consecutive hours all PPC lignite plants of Western Macedonia and Megalopolis https://twitter.com/The_GreenTank/status/1270315522769510403 stopped working after 64 years of uninterrupted operation. It was a two-day milestone. The total absence of lignite in energy demand coverage was also noted for 24 consecutive hours from the 10th of August to the 11th in 2020.

Causes of reduced lignite production

This drastic reduction of lignite production is the result of the combination of many parameters, most of which are linked to the European Union (EU) climate and environmental policy.

The first and most important reason is the European Directive for the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS). Since 2013, when the free emission allowances to the electricity sector ceased –with some exceptions that do not concern Greece– PPC has been forced to pay for every tonne of carbon dioxide (CO2) emitted by its plants. Characteristically, despite the low CO2 prices, 2013 was the first year that PPC’s lignite activity presented damages according to its official data included in the updated Just Transition Development Plan Ministry of Environment and Energy (December 2020) “Updated Master Plan of Just Transition Development of lignite areas (in Greek) https://bit.ly/SDAM2020 ]. The surcharge of lignite kWh and the corresponding losses of PPC's lignite activity became even greater from the second half of 2017 onwards, due to the spike in CO2 prices. That was the result of the changes decided by the three European institutions during the period 2015-2017 in the context of the Directive’s revision.

The Directive will be revised again in 2021 in order for the European legislation to align with the new climate target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels. As the new target is way more ambitious than the last one, it is predicted that the harmonisation of the Directive will lead to even higher CO2 prices. It is worth mentioning that BloombergNEF (BNEF) estimates that the cost of CO2 will exceed 40 euros per tonne in 2023, while by 2028 it will go above 50 euros per tonneBloombergNEF (November 2020) “EU Climate Goals Accelerate Eastern European Decarbonization” https://bit.ly/2LB0oX8

The second reason that contributed to the reduction of lignite production is the implementation of the Industrial Emissions Directive in 2016 in combination with the introduction of stricter emission limits for sulphur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, microparticles, heavy metals and other pollutants gases in 2017. These changes forced expensive upgrades to the lignite plants triggering further financial burdens in lignite industry.

The third crucial parameter was the abolition of subsidies to the lignite industry through their participation in power sufficiency mechanisms. The European Regulation on the operation of the electricity market, which was finalised at the end of 2018, completely banned the subsidy for the operation of new lignite plants, while the subsidy of existing ones cannot continue after July 2025. This decision, in combination with the developments mentioned above, eliminated every prospect of sale of PPC lignite plants which was attempted twice in 2019 leading to complete failure.

What is more, for years, mature technologies on Renewable Energy Sources have been cheaper than lignite. The final selling prices of electricity in the auctions of new wind and photovoltaic parks are now lower than € 54/ΜWh and € 46/ΜWh respectivelyDecision No. 1142/202 of Regulatory Authority for Energy (RAE). https://bit.ly/3pcEDf5 . That cost is way lower than the one necessary for lignite electricity production estimated by PPC in 2019 when it was trying to sell its plants, and it ranged between € 65 and € 70/MWh Energypress.gr, 22.05.2019 https://bit.ly/2OTa14K . Since then, the CO2 prices have significantly raised and so has the cost of lignite kWh.

As the Greek lignite has, by far, the lowest heating value in Europe, it is the most vulnerable to any changes with financial impact compared to the lignite industry of other European countries. In 2019, there were still some lignite plants in Germany that were barely making a profit Ember (2019) “The cash cow has stopped giving: Are Germany’s lignite plants now worthless?” https://bit.ly/3aizJsw, while in the same period in Greece the situation was completely different The Green Tank (September 2019).“The economics of Greek lignite plants: The end of an era.” https://bit.ly/3mvIeTw .

In view of the above and given the stricter European climate policy and the shift of all European economy towards clean energy forms as directed by the European Green Deal The European Green Deal sets as target to become the first climate neutral continent by 2050., the end of lignite in Greece is irreversible. However, the new reality is accompanied by great challenges.

The threat of turning to fossil gas

The key issue at national level is how to fill the energy gap that will be created by rapid independence from lignite. In addition to the increased penetration of RES, the current NECP includes 2.1 GW of new fossil gas plants. Compared to the previous NECP that did not include delignification, the current Plan includes an 80% increase of electricity production from fossil gas in 2030. The IPTO adequacy study that followed the NECP suggests the construction of three new fossil gas plants of a 2.3 GW total power in 2030. However, this planning is wrong for a number of reasons.

To start with, the evolution of the energy mix in 2020 shows that RES are already able to absorb the "shock waves" of delignification. As can be seen from the official data of IPTO (Chart 3), the decrease by 50.6% of lignite production in the first ten months of 2020 was more than offset by the increase in RES production (+18.6%) and much less than decrease in demand (-6.2%), increase in net imports (+5.8%) and even less than the increase in fossil gas (+4%). In fact, during the first ten months of 2020, some RES and big hydropower plants produced more than the fossil gas plants (14,676 GWh vs 14,663 GWh).

The most important reason for avoiding the link of the country’s energy future to fossil gas is the new European climate target. A study of the National Technical University of Athens shows that in order for Greece to manage to be in line with the new European target for emissions reduction by 55% by 2030 in comparison to 1990 levels, the RES share in the final gross energy consumption in 2030 must be between 83% and 88% P. Capros, E3M (September 2020) “PRIMES Model Scenarios for the EU’s Green Deal” https://bit.ly/2WpgEwM. It is a high increase compared to the 61% of the current NECP which does not leave any room for new fossil gas plants.

Furthermore, the financing sources for fossil gas are running out, one after another. The European Investment Bank (EIB) will not finance any fossil fuel energy project after 2021 EIB (November 2019). “EU Bank launches ambitious new climate strategy and Energy Lending Policy” https://bit.ly/38cOJWb. This kind of investment will not be eligible by the newly founded European Just Transition Fund N. Mantzaris, “No to fossil gas from the Just Transition Fund”, energypress (10 December 2020) (in Greek) https://bit.ly/3aljlaS, neither will be in the sustainable investments list of the European Sustainable Taxonomy Regulation.

Under these circumstances, it is clear that any plan for new fossil gas plants must stop and the NECP must be amended immediately setting new, higher targets of RES penetration and decrease of electricity production from fossil gas.

The transition of lignite regions

The second great challenge of delignification is socio-economic and it is related to the two lignite areas of the country, the Western Macedonia region and Megalopolis. For decades, the residents of these regions sacrificed the areas’ natural resources, their health and their quality of life to provide electricity to the country.

The challenge for these areas in Greece is clearly greater than the one facing other similar regions in the EU. First of all, due to the inaction of those in power all these years that the future of lignite was already predetermined, our lignite areas are called, faster than any other in the EU, to make huge changes in their production model. And these changes are practically impossible to be completed within the three years that remain until the overall withdrawal of the existing lignite plants.

Moreover, the lignite areas of Greece have to start from a worse position given the high unemployment that already plagues them. According to official Eurostat data, Western Macedonia region and the Peloponnese are ranked first and sixth respectively in unemployment and long-term unemployment among the 96 regions of the EU-27 where either lignite or coal is mined or burned in power plants, or both (Chart4).

In addition, the degree of dependence of local economies in Greece’s lignite areas on lignite activity is extremely high, making their transformation even more difficult. According to the research conducted by The Foundation for Economic and Industrial Research (IOBE) during the 2008-2017 period, the energy and mining sector contributed in average 49% of the Gross Value Added (GVA) in Kozani, 36% in Florina and 25% in Arkadia ΙΟΒΕ (August 2020) “Delignification of the electricity production: socio-economic impact and offsetting actions” (in Greek) https://bit.ly/3mtEDVW.

Under these circumstances, it is not surprising, at all, that there is unrest and great concern in the local communities of the country’s lignite regions. A recent public opinion survey “Delignitisation and Just Transition to the post-lignite era: What are the views of the citizens in the lignite regions?” (in Greek) https://bit.ly/34kxz81 conducted by the Green Tank, the professor of the University of Athens Emmanuela Doussis, diaNEOsis and the polling company MARC showed that citizens are overwhelmingly pessimistic about the prospects of their region as they believe that the future holds high rates of unemployment, impoverishment and leaving of young people. This negative attitude is certainly related to the objective difficulties of the transition but also to the prevailing ignorance. Only few citizens know the existence of next-day plan and proposals while there is a great deal of ignorance and confusion regarding the existence and amount of financial resources that will be available for the transformation of the local production model. In addition, the pessimism of the citizens is related to the fact that from the announcement of the decision for delignification until today the local public debate is dominated by efforts to overturn the decision and extend the operation of the lignite plants. Only a small number of the suggestions or ideas for other economic activities to which the local economy should turn in the post-lignite era become public. The optimistic part of the survey is that 1 in 2 residents of these areas, mostly the young people, see the delignification as an opportunity for change and support the shift to the primary sector and the clean energy technologies for the transformation of the local economy. Finally, they believe that the increased participation of the society is a necessary condition for the success of the transition and they demand decentralisation of the government with enhanced participation of the local and regional authorities.

Based on the results of the research, it becomes clear that a multi-participatory governance system is required in the phase of implementation of the transition plan along with much more extensive information to and consultation with the citizens of the lignite areas. Moreover, in addition to the stable and seamless funding, and given that the transition will take time, it is truly important to have a broad consensus among the political parties in national and local level regarding the transition issues. This is far from the current situation where the parties are still arguing about the past, about whether the delignification decision was right or not and about the extension of the operation of the lignite plants, when the lignite production is de facto collapsing.

Finally, in order for the transition to succeed, it is of the utmost importance to be green. This is exactly the direction given by the European Green Deal as the new EU growth strategy. And as the recent lignite history has shown, the political will in the EU can be rapidly transformed into legislation and diversion of funding. It would therefore be a disastrous mistake to invest the finite resources that the country has for the transition of its lignite areas to fossil fuel infrastructure and not to those that will be environmentally and economically sustainable in the long run.