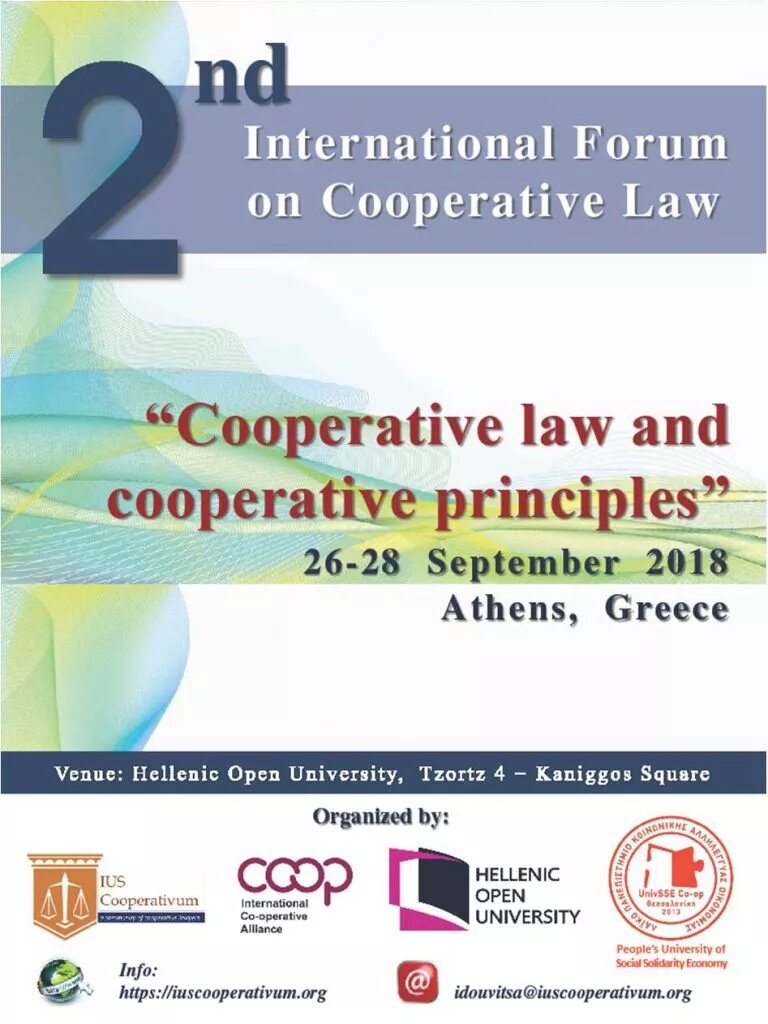

The general theme of the 2nd international forum was “Cooperative Law and Cooperative Principles”. Within this framework, special emphasis was placed on the significance of cooperative principles for cooperative law, research and education in the field of cooperative law, and an exchange of views on cooperatives between lawyers and economists.

A number of accredited scholars in the field of cooperative law, cooperative economics and Social Solidarity Economy participated into the proccedings of this interesting international forum. On the first day, the organizers inaugured the proceedings of the forum together with opening remarks by Mr. Bruno Roelants, the new general director of the International Cooperative Alliance, and an ILO statement messaged by Mrs Simel Esim, Cooperatives Unit manager. Professor Hagen Henry, an accredited scholar in the field of cooperative legislation, contributed with an introduction to the program and noted the latest developments in cooperative law.

The forum was organized along the following sessions:

- The legal relevance of the cooperative principles for cooperative law with the participation of accredited scholars from Spain, Brasil and Greece.

- A round-table between lawyers and economists in order to foster interdisciplinary exchange

- Cooperative law and the legal framework of the social economy with a special emphasis on the recent legal framework on Social Solidarity Economy in Greece and the main challenges posed ahead as well as a presentation on the potential to introduce a legal framework for the transfer of failed enterprises to worker cooperatives.

- The legal relevance of the cooperative principles for other fields of law covering the necessary supplementary legal framework and interesting aspects such as the gender dimension, work relations within cooperatives, relation of cooperatives with Corporate Social Responsibility.

- Legal requirements for specific types of cooperatives by sector (e.g. agricultural, banking, energy cooperatives).

- Legal requirements for specific types of cooperatives by governance/structure (e.g. workers’ cooperatives, multi-stakeholder cooperatives, social cooperatives).

- Cooperative law and human rights with emphasis on constitutional provisions with regard to cooperatives.

- The increased need of harmonization and unification of cooperative law at regional, national and international levels.

- The role of cooperatives within the general context of globalization with regard to the latest technological developments and the background of the financial crisis.

- Existing educational programs in the field of cooperative law.

- Tools for the research and study of cooperative law.

Sofia Adam, program coordinator of Heinrich Boell Stiftung Greece, participated in the panel addressing cooperative principles and the legal framework on Social Solidarity Economy with special emphasis on the Greek case. Her presentation was based on the results of the recent publication titled: “The legal framework of Social Solidarity Economy in Greece. The experience of public consultation and a first assessment of Law 4430/2016” (available in Greek).

At first, the presentation addressed the question of definitions and in particular the convergences and divergences between social and solidarity economy as concept and practice. An increased dialogue and exchange of views and experiences between traditional social economy actors (i.e. cooperatives) and the new solidarity economy initiatives is increasingly taking place and has recently led to the synthesis into the term Social Solidarity Economy adopted by international networks such as RIPESS. This synthesis denotes the intention of mutual exchange towards a more unified political vision while acknowledging differences in its constituent parts.

The presentation also shed some light on the relevance of the international cooperative principles as potential building blocks of the Social Solidarity Economy movement. According to prior work of accredited scholars in cooperative legislation, cooperatives are seen as distinct organizations because they are member-centered and as such they are conducive to a sustainable development paradigm defined by economic security, social justice, ecological balance and political stability. However, these linkages cannot be taken for granted for a number of reasons. First, despite the long tradition of cooperative legislation, there is still a debate on how the international cooperative principles are translated into enabling cooperative legal frameworks. Second, there is a growing tendency towards the harmonization and unification of cooperative legislation at the international level in conjunction with an increasing “companization” of the cooperative legal form (away from the distinctiveness of the cooperative identity). Third, the alleged inherent social character of cooperatives cannot be automatically equated with the broader societal concerns put forward by the Social Solidarity Economy from a transformative perspective.

The Greek Law 4430/2016 endorsed the values and principles expressed by SSE actors as a social movement in Greece and abroad. However, despite the good intentions, a number of deficiencies are identified which might block exactly the process that the Law intended to enable in the first place. First, certain provisions of the new legal framework pose challenges for the inclusion of traditional social economy actors (i.e. agricultural cooperatives) for reasons that do not reflect a different value-base but simply a misalignment among the provisions of the fragmented cooperative legal framework and the respective provisions of Law 4430/2016. Second, Law 4430/2016 has a dual intention: a) it introduces/modifies specific legal entities (worker cooperatives and social cooperative enterprises respectively) and affords the legal status of a Social Solidarity Economy agent to other existing legal entities given that they fulfill certain criteria. However, this dual intention led to a misalignment of criteria between the self-righteous SSE agents (social cooperative enterprises and worker cooperatives) and other legal entities potentially granted the status of a SSE agent which is not coherent from a policy perspective. For example, the other legal entities are required to enforce equitable payment schemes and participate in horizontal networks whereas the self-righteous SSE agents are not. Finally, certain provisions signify a tendency towards over-regulation as is exemplified by the requirement of all SSE agents to have 25% of their turnover as wage-labour expenditure regardless of the specific productive activity undertaken.

In conclusion, the unification and harmonization of cooperative legislation in Greece must be undertaken with a dual purpose: a) to explore how the international cooperative principles can be transformed into legal provisions, b) to renew the interest in cooperative legislation in order to safeguard the distinctiveness of the cooperative identity. This process should go hand in hand with a procedure of institutional consolidation where a clear mandate is given to the newly formed SSE special secretary to supervise and approve all relevant legislation in the field, meaning that no new legal framework is to be proposed without a clear check and balance of coherence with the overall strategy and legal provisions of SSE in Greece.

If these steps are taken in a systematic and persistent manner, SSE initiatives and networks might be able to flourish and create their own, autonomous peer monitoring mechanisms and contest their values, principles and operational guidelines within their own procedures of democratic deliberation.

For access to available presentations in full, please click here.